In recent weeks, more and more people with legal status — green card holders and visa recipients alike — have faced detention or deportation, seemingly based on information found on social media about them or on their devices.

Documented spoke to digital security and immigration experts about precautions people can take to protect their data and devices. Below are some of their recommendations.

Know your risk level

In order to assess your risk, you have to take into consideration your immigration status, travel history and the data captured on your social media and stored on your devices when making choices about what precautions to take. It’s unclear exactly what immigration officials might be looking for when determining whether someone should be detained or deported, but news reports have highlighted that students and travelers who have been detained have liked or shared pro-Palestine posts, had images of Hezbollah leaders on their phones or had messages on their devices that were critical of President Donald Trump.

Immigration lawyer Ginny Nunez also said it might be helpful to think about your country of origin in the context of the news at this moment.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), a nonprofit dedicated to defending civil liberties in the digital world, recommends building a threat model around your situation, which is akin to planning out the worst-case scenario for what could happen if parts of your data were not secured. Looking at these scenarios can help you understand how to prioritize what data to protect and how much energy you may want to put towards each area. Their guide on this can be found here.

Social media

Recently, USCIS announced that it will collect the social media information for immigrants applying for green cards or citizenship and ICE has signaled that the agency wants to hire contractors to monitor social media.

The easiest way to avoid unwanted surveillance of your social media accounts is to simply have none. It might be worthwhile deleting accounts if they are not vital to your professional or personal life. If you’re not ready to fully delete your accounts, you could try to scrub parts of your social media history, too. For some accounts, this might mean that you have to go through past posts and delete them. For others, like X, formerly known as Twitter, there are services that can automate deleting posts, such as Claw Back Your Data.

Another way to approach your social media, said Klosowski, is to compartmentalize your online presence. For instance, he has public accounts on X and LinkedIn for his professional work where he shares only work-related information and keeps a private Instagram account for his friends and family.

Making your account private does not fully protect your data. For example, law enforcement may still be able to access messages from your account by obtaining a warrant, but it cuts out a layer of surveillance from companies that may scrape and aggregate data from public social media accounts. Nunez said that she has heard of judges mentioning information they find on social media in court and that social media content had come up during spousal interviews with immigration officers. Turning these accounts private may also help in these instances, she said.

Block Party is a service that can help you adjust the privacy settings of multiple social media accounts. To use the service, you will need to log into your accounts on a computer and install their browser extension on Chrome. After setting it up, Block Party will recommend the best privacy settings for each of your social media accounts.

While you’re at it, Klosowski recommends going through your friends list and ensuring only people you trust have access to your posts.

Ultimately, Nunez said that it’s questionable just how protected our information online is.

“Social media is only as private as the owners [of the companies] want it to be, right? And we cannot be blind to the fact that every social media owner is very cozy with this administration. So even if you have your account is private, I don’t know how private that’s going to be for the next few years,” she said.

“I don’t want to smother people, but if it’s in your best interest to stay here, than to be returned, then I would say, think about how you what you’re putting on your phone, as if your mom and or dad, […] is watching your phone on a daily basis. That’s how I basically approach what’s on my phone,” she said.

Jerome D. Greco, digital forensics director at Legal Aid Society, also told Documented it could be worthwhile to pay for a service to remove your data from people-search websites. Consumer reports recently published a helpful guide on various services such as Deleteme or EasyOptOuts that can help remove your information from those sites.

Traveling with your devices (that includes phones and laptops)

While the U.S. Constitution puts a lot of limits on what searches the government can conduct on your devices, these protections are weaker at the border, said Nunez.

Multiple courts have ruled that border patrol agents are allowed to search the devices of people crossing the border into the U.S., said Greco.

This means all your devices, including phones and laptops, are subject to search by border patrol.

Since March, there have been at least two incidents where people were denied entry to the U.S. based on information found on their phones. A Rhode Island doctor and visa holder was deported to Lebanon after U.S. authorities found photos of a former Hezbollah leader in her deleted items folder on her phone. A French scientist was denied entry to the U.S. when immigration officers found messages on his phone in which he expressed criticism of Donald Trump.

This means it’s important for you to consider what data you carry with you during your travels. The EFF’s guide to protecting your data at the border suggests that you might want to consider using temporary devices, deleting data from your phones and laptops or moving a lot of data to the cloud.

补偿终止但盗窃不止!纽约近9千起粮食券被盗案难获赔

There are multiple ways in which you can reduce some of the sensitive data you carry with you on your travels. Immigrant ARC, a New York-based community of legal advocates, recommends deleting all apps from your phone that are not essential for travel and permanently removing items in your recently deleted folder. You may also want to scrub the browser history from your browsers on your phone (guide for iPhone and Chrome/Android). Greco recommends using message apps like Signal and changing your chat settings to automatically delete messages after a specific time frame.

To safeguard the data that you do end up taking with you on your devices, you may want to disable Face ID or fingerprint locks on your phone, which are weaker than passwords.

If you find yourself at a border, border agents may ask you to unlock your phone or laptop. You do not have to comply, but you do face risks: While agents must let U.S. citizens enter the country, they might raise questions about your status if you are a green card holder or deny you entry if you are on a visa. The EFF recommends that you stay calm and do not lie to agents, which can be a crime.

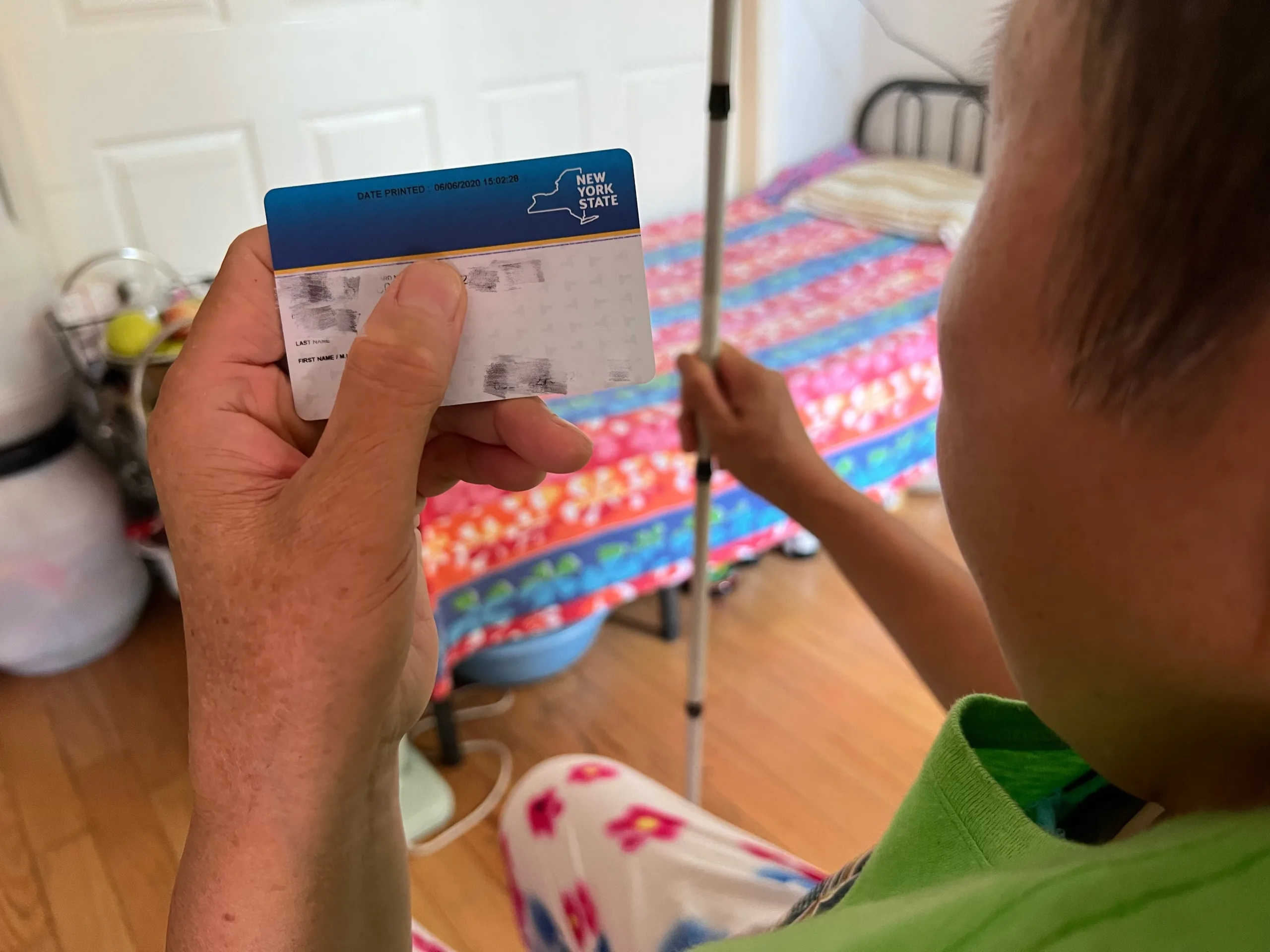

Whatever may happen, you should have your legal documents, a copy of your legal documents, and the number of an immigration lawyer with you while traveling.