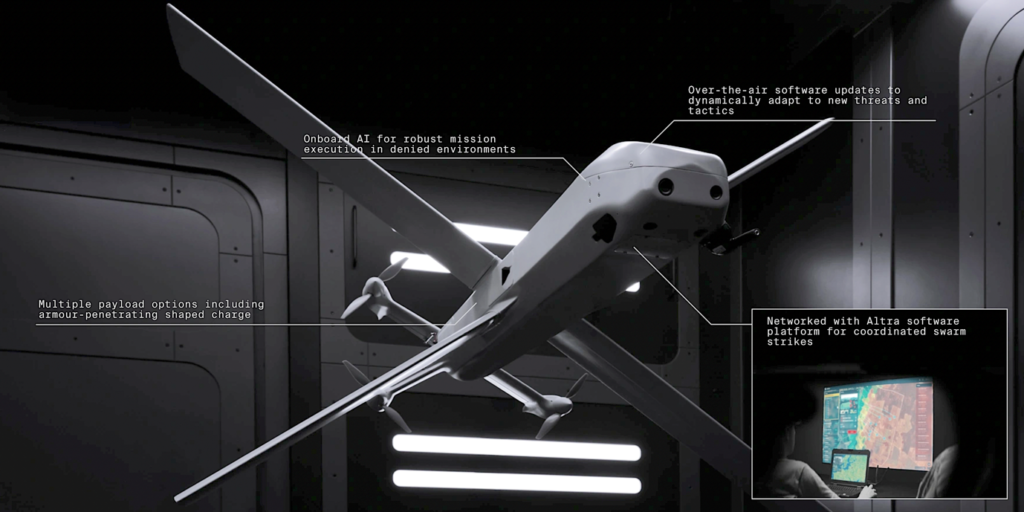

AI-generated image

The history of drones (unmanned aerial vehicles, or UAVs) dates back over a century. The concept emerged in the mid-19th century, with experiments involving balloon-based bomb delivery systems. However, the first practical UAVs were developed during World War I. The first pilotless aircraft was the Ruston Proctor Aerial Target, designed in Britain in 1916 by Archibald Low. It was intended as a flying explosive device to take down enemy Zeppelins or ground forces, but was never actually deployed in combat. Around the same time, the U.S. Army developed the Kettering Bug, an early cruise missile designed by Charles Kettering, which could fly a predetermined distance before dropping its payload but was also never used in battle before the war ended. A bit later, in the 1930s, the British developed the DH.82B Queen Bee, a remote-controlled target drone for military training. The U.S. followed in the 1940s, producing radio-controlled drones such as the Radioplane OQ-2, the first mass-produced UAV (over 15,000 units made) used as a target drone for military training. After World War II, drones evolved rapidly, due to the increased interest and need for intelligence gathering.

The U.S. Ryan Model 147 ‘Lightning Bug’ became one of the first long-range reconnaissance UAVs used extensively in the Vietnam War (1964–1975). The Soviet Union also experimented with UAV technology but focussed more on missile-based systems. The Israeli military played a key role in modern drone warfare, developing UAVs used effectively in conflicts such as the 1982 Lebanon War (IAI Scout and IAI Pioneer). The U.S. adapted Israeli technology, developing the MQ-1 Predator, which later became a cornerstone of drone-based warfare. By the 1980s, drones were already being equipped with better cameras, infrared sensors, and real-time data transmission capabilities. The 1991 Gulf War, when the U.S. extensively used the RQ-2 Pioneer, demonstrated the effectiveness of drones in battlefield surveillance. The first modern surveillance drone used in extensive military operations, the RQ-1 Predator, was developed in 1994 by General Atomics. A weaponised version, the MQ-1 Predator, was first used in Afghanistan after 2001, marking the beginning of drone-based warfare.

The explosion of consumer drones began with DJI, a Chinese company founded in 2006, which launched the Phantom series in 2013, making drones widely accessible to the general public.

Today, drones are used in all kinds of activities, from journalism, agriculture, disaster relief, and law enforcement to surveillance and delivery services. Military drones have also become autonomous, with models like the MQ-9 Reaper, capable of independent operations.

The war in Ukraine has shown how low-cost drones and consumer drones modified for combat can effectively change modern warfare. The ever-increasing use of drones also presents ethical and security concerns. Governments and private companies use drones for surveillance, raising privacy concerns (for example, China’s use of drones for population monitoring). The use of drones in warfare (such as U.S. strikes in the Middle East) has raised concerns over accuracy and accountability. Others wonder whether AI-powered drones should be allowed to make life-or-death decisions in live combat. In more recent years, drones have also been used for smuggling, illegal surveillance, and even attacks, like the 2018 Venezuelan presidential drone attack, when two small drones carrying explosives were detonated while President Maduro delivered an outdoor speech. Consumer drones can be hacked and hijacked, posing security risks. Today, we see a rise in self-flying drones that use AI for navigation, object detection, and target tracking, while the military is experimenting with autonomous drones, which are set to revolutionise warfare.

While companies like Amazon, Google, and UPS have started to implement drone deliveries, Japan and the UAE are flirting with the idea of using drones for passenger transportation (air taxis) to reduce traffic congestion.

Drones could also be used for environmental and humanitarian purposes. Reforestation drones can plant up to 100,000 trees per day. Medical drones (like those already used in Rwanda) can transport blood and vaccines to remote areas.

Drones also became popular as toys starting in the early 2010s, thanks to advancements in battery life, miniaturisation, and lower production costs. The Parrot AR Drone, launched in 2010, was one of the first toy drones controlled via a smartphone, making drones more accessible beyond military or industrial use. Three years later, the Syma X5C became a best-seller due to its affordability and built-in camera. The launch of DJI’s mini drones allowed children to fly drones with beginner-friendly controls. Companies started adding altitude hold, obstacle avoidance, and auto-hover features, making them easier and safer for children. Toy drones also became part of the educational process, teaching children about coding and robotics. By the late 2010s, drones had already become a mainstream toy category, available in most stores, despite the relatively many potential accidents, ranging from propeller cuts and crashes to property damage and even battery explosions.

However, when we talk about drones, we should also consider some major aspects shaping their impact today. First, we need to address the need for clear international regulations regarding their use. Drones, including toy models, can pose a serious threat to aviation if flown near airports or flight paths. Drones can get sucked into jet engines or crash into the windshields of airplanes or helicopters. A drone flying too close to a plane may distract the pilot or cause an emergency manoeuvre. Some drones operate on frequencies that may overlap with aviation communication signals, causing navigation issues. That is why several international institutions regulate their presence. ICAO (International Civil Aviation Organization) works on integrating drones into controlled airspace. EASA (European Union Aviation Safety Agency) sets drone operation rules in the EU; the FAA (Federal Aviation Administration, USA) requires drone registration for commercial use and restricts flights near airports. Most countries have set the maximum altitude limit for flying drones to 120 metres. There are no-fly zones near airports, government buildings, or military bases. Commercial drone operators are required to register and license their drones. Both the EU and the US require drones over 250 grammes to be registered by their pilots. Geo-fencing technology is used in many areas to automatically block drones from flying in restricted zones. Some countries, like China, Russia, or the UAE, have even more severe restrictions.

China and India imposed strict drone bans in their capitals, Beijing and New Delhi. In 2022, the UAE banned all recreational drones after reports that they were used for unauthorised surveillance. As of January 2025, the General Civil Aviation Authority (GCAA) and other UAE authorities lifted the conditional ban on individual drone use. However, only UAE residents and citizens are permitted to fly drones, provided they are registered, approved by the GCAA, and hold a certified drone pilot training certificate. The EU has elaborated its own regulations to safely integrate remotely piloted drones into European airspace. Additionally, in June 2018, the European Council adopted new proportionate and risk-based rules that enable the EU aviation sector to grow and make it more competitive. One regulation refers to the registration threshold for drone operators: if the drones can transfer more than 80 joules of kinetic energy upon impact with a person, then they should be registered. Meanwhile, the European Commission predicts that by 2035, the European drone sector will directly employ more than 100,000 people and have an economic impact of over €10 billion per year.

Chinese drone maker DJI is the world’s largest drone manufacturer, with a market share of more than 70 percent worldwide. The company offers a wide range of drones for both professional and consumer use in almost 100 countries. China has the most cost-effective drones for domestic use and export, while it is also the spare parts supplier to most other drone manufacturers in the world.

Military drones represent a significant part of the global drone market; its size is expected to grow by 13.1 percent between 2022 and 2028. (Source: https://brandessenceresearch.com)

The US holds over 13,000 military drones, making it the largest military drone fleet globally.

Lockheed Martin and Boeing are among the top five producers worldwide. Lockheed Martin, a leading U.S. defence contractor founded in 1995, develops high-tech military drones for surveillance, reconnaissance, and combat operations. The company also produces autonomous systems, including AI-driven UAVs, to enhance battlefield capabilities. Boeing manufactures advanced military drones, such as the MQ-28 Ghost Bat, a loyal wingman drone designed to support manned fighter jets. Boeing integrates cutting-edge AI and swarm technology into its drone programmes, enhancing operational efficiency in combat scenarios. Northrop Grumman is another leading defence contractor, developing and producing military drones and unmanned systems. The company’s Global Hawk and Triton high-altitude long-endurance drones provide critical intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities to the U.S. military.

Israel is also one of the world’s leading producers and exporters of military drones. The country has been at the forefront of such technology for decades, developing a wide range of UAVs for intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance (ISR), and combat roles. Israel’s defence exports have doubled in less than a decade, reaching a record of $12.5 billion in 2022, according to the Israeli Ministry of Defence.

Turkey is already a recognised supplier of innovative yet affordable drones and has become a strong exporter. While many Turkish companies, such as Baykar, Turkish Aerospace, and STM, produce drones, the combat drones produced by Baykar—especially the Bayraktar TB2 and AKINCI—are in high demand due to their low prices and high efficiency, which they have proven in conflicts where they have been successfully used in recent years.

While Iran has banned any kind of use of drones, which are immediately confiscated when entering the country, locally manufactured ones like the Shahed-136 are considered some of the most cost-effective today. Their price, between US$20,000 and US$50,000 per unit, is significantly lower than most other precision-guided missiles and makes them very attractive to potential buyers.

Europe is slowly trying to keep up with this trend in drone production, fuelled also by the recent years’ complicated situation on the continent and also by the even more recent and alarming declarations and moves of US President Trump. AltiGator is a European drone manufacturer company from Belgium, founded in 2008. Drone Volt, based in the Paris region, has been manufacturing drones since 2011. The company has 60 employees and subsidiaries in Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Canada. Tekever from Portugal designs and builds drones for aerial surveillance that can serve as the communication and navigation hub for swarms of smaller drones. WB Group is currently Poland’s leader in designing and production of drones. The country has invested immensely in recent years in military equipment.

Lithuanian drone manufacturer RSI Europe was founded after Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Tomas Milašauskas, its CEO and co-founder, told Business Insider that ‘the company was born out of fear of what a Ukrainian defeat could mean for Europe’s future security’. In the same context, the German drone manufacturer Quantum Systems, which opened its first facility in Ukraine in April 2024 and currently operates two plants in Ukraine, is planning to double its drone production in the country. ‘We stand for everything that defines our free and democratic societies’, it is stated on their own website.

The completion of German AI start-up Helsing’s first Resilience Factory (RF-1) in the southern part of the country marks a significant milestone in bolstering Ukraine’s defence capabilities amid its ongoing conflict with Russia. This facility is the first step in a series of planned Resilience Factories across Europe, designed to provide sovereign and scalable manufacturing capacities for advanced defence technologies. These drones are equipped with artificial intelligence, enabling resilience against electronic warfare, boasting a range of up to 100 kilometres and designed for precision strikes against armoured vehicles and infrastructure. In addition to Helsing’s contributions, the international Drone Capability Coalition, co-led by the UK and Latvia, has placed contracts worth 45 million pounds to supply 30,000 drones to Ukraine. The combination of advanced technology, scalable manufacturing, and international cooperation is poised to play a crucial role in strengthening Ukraine’s defence posture.

Helsing plans to ‘take a distributed approach towards mass manufacturing these systems across Europe, allowing individual nation states to produce locally and ensure sovereignty of production and supply chain’. (Gundbert Scherf, co-founder of Helsing)

Sweden’s Saab and Helsing have established a strategic partnership to integrate Helsing’s advanced artificial intelligence technologies into Saab’s defence systems, enhancing its capabilities across various platforms, including drones. Although Saab primarily develops drones for reconnaissance and surveillance rather than armed ones, given the increasing demand for UAVs in modern warfare, it could expand its portfolio in the future.

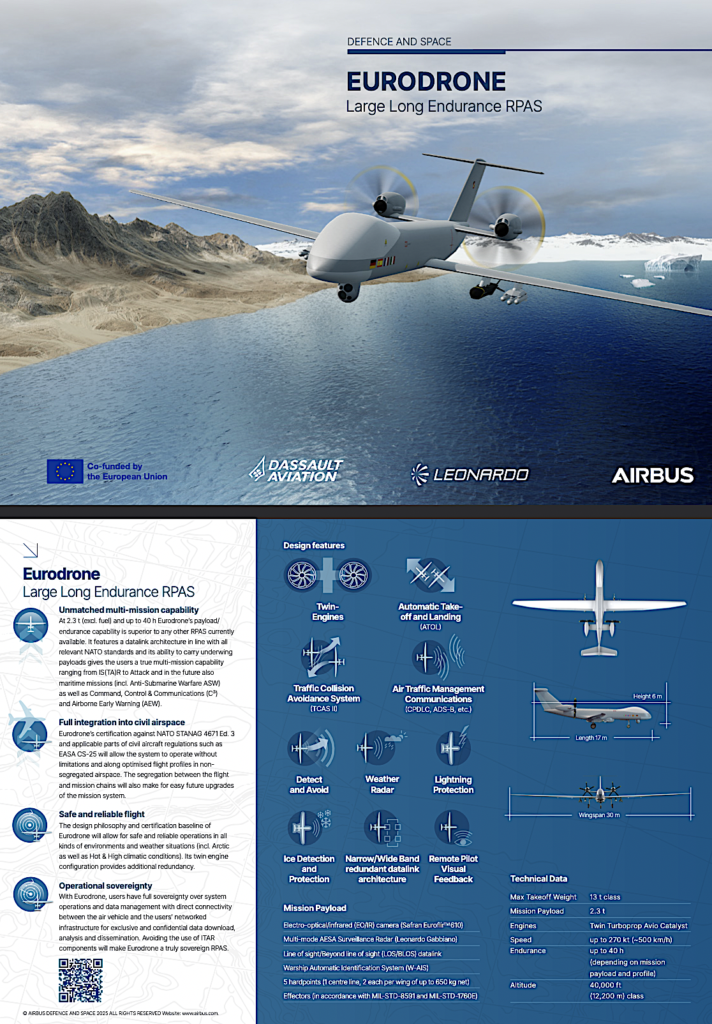

The Eurodrone, a remotely piloted aircraft system developed by Airbus, is designed to carry out long-endurance missions for intelligence, surveillance, target acquisition, and anti-submarine warfare. The Eurodrone will be able to fly in non-segregated airspace, carry weapons, offer naval anti-submarine warfare as well as electronic warfare capabilities, featuring a 2.3-tonne payload, 40 hours of autonomy, and a maximum altitude of 45,000 feet. Expected by mid-2027, it has already received orders from Germany, France, Italy, and Spain.

The establishment of Resilience Factories underscores a broader European initiative to achieve self-sufficiency in defence manufacturing. By localising production, these facilities aim to rapidly scale manufacturing rates to tens of thousands of units in response to conflicts, thereby reducing reliance on external suppliers. The problem is that most drones assembled in Europe still inevitably use spare parts imported from China, which is a significant liability in trade or war scenarios.

China dominates the global supply chain for drone components. Many drone parts, including motors, batteries, flight controllers, and cameras, are produced in Shenzhen, the heart of the global electronics industry. Chinese suppliers offer high-quality components at very competitive prices. However, some manufacturers in the U.S., Europe, and Israel have recently started to find alternatives for specialised components from South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan (for sensors and semiconductors) or Germany and Switzerland (for precision engineering parts). Considering the recent trade tensions between China, Europe, and the U.S., it is a matter of security for Europe to be able to produce its own drones without any outside interference in the supply chain. Europe is aiming to produce drones entirely with European-made components. The European Economic and Social Committee (EESC) has emphasised the importance of integrating the European Drone Strategy with the European Defence Industrial Strategy to support domestic production of high-quality drones. This strategy, introduced in 2022, prioritises the development of a safe and efficient drone ecosystem while creating a large-scale European drone market, valued at more than €20 billion and potentially generating 145,000 jobs by 2030.

However, achieving complete self-sufficiency presents challenges because of the fragmentation of the European drone industry and limited cross-border cooperation. Europe needs standardisation and cross-border investments, incorporating cutting-edge techniques like 3D printing to improve efficiency. The increase in military spending, partly driven by geopolitical threats, has spurred investment in European defence, including in companies focused on drone technology. This market is projected to grow by nearly 40 percent annually.

In the context of recent geopolitical events, enhancing Europe’s independent defence capabilities is imperative. Developing strong and advanced indigenous drone manufacturing can address some of these concerns by providing superior surveillance and combat capabilities tailored to the continent’s defence needs. It is also essential for ensuring strategic autonomy, fostering economic growth, and enhancing Europe’s position on the global stage.