Mumbai: While on holiday in Australia in December 2023, Abhinandan Lodha woke up to a string of missed calls from Amitabh Bachchan. The countdown to the Ayodhya Ram temple consecration had begun, and the actor wanted to be first in line for a plot at The House of Abhinandan Lodha’s Ayodhya project. The city was trying to shed its violent, communal past with a promise of faith, development, and luxury real estate—and this seven-star offering was part of the pitch.

“He [Bachchan] explained the situation to me — he told me that what I was doing was making land available to every single Indian. It’s a noble cause and we’re doing it with the highest level of transparency,” said 43-year-old Abhinandan at his office in Lodha Excelus in Mahalaxmi, the quintessence of business and power in Mumbai.

Inside, though, his office is remarkably ordinary. Sunlight streams in, the furniture is functional, and there’s little to betray that this is the workspace of a man whose father, Mangal Prabhat Lodha, is India’s eighth richest person—and a minister in the Maharashtra cabinet.

When referring to Ayodhya, home to the Ram Janmabhoomi Mandir, Abhinandan adds a suffix of reverence. It becomes Ayodhya-ji. He has a deliberate manner and describes himself as a voracious reader, currently immersed in a biography of RSS icon VD Savarkar. His company calls itself a New Generation “branded land leader”. His personal ethos, he says, is that every Indian should own a piece of land that can “create international wealth”.

But the original house of Lodha is divided, with brother pitted against brother. The House of Abhinandan Lodha (HoABL), founded in 2020, is trying to step out of the shadow of Macrotech Developers (formerly Lodha Group)—the mighty Rs 1.36 lakh crore real-estate construction company founded by their father and now helmed by Abhinandan’s older brother, 46-year-old Abhishek Lodha.

HoABL’s Ayodhya venture—’The Sarayu’, where Bachchan bought a 10,000 square foot plot—is the young company’s biggest project to date.

From a business standpoint, it was a smart bet. Land and gold are India’s oldest obsessions, and Abhinandan wanted to make land ownership in Ayodhya aspirational for NRIs, celebrities, and faith-driven investors.

It didn’t quite go as planned. It began well with Abhinandan Lodha stepping into real estate, seeing healthy appreciations, and investing over a hundred crores in start-ups, but quickly got derailed by an IPR battle and what many call a sibling rivalry. It boiled down to what the ‘real’ Lodha is, the business empire founded by the businessman and seven-time Malabar Hill MLA Mangal Prabhat Lodha. It is yet to be seen whether the feud will have any material impact on his business dealings.

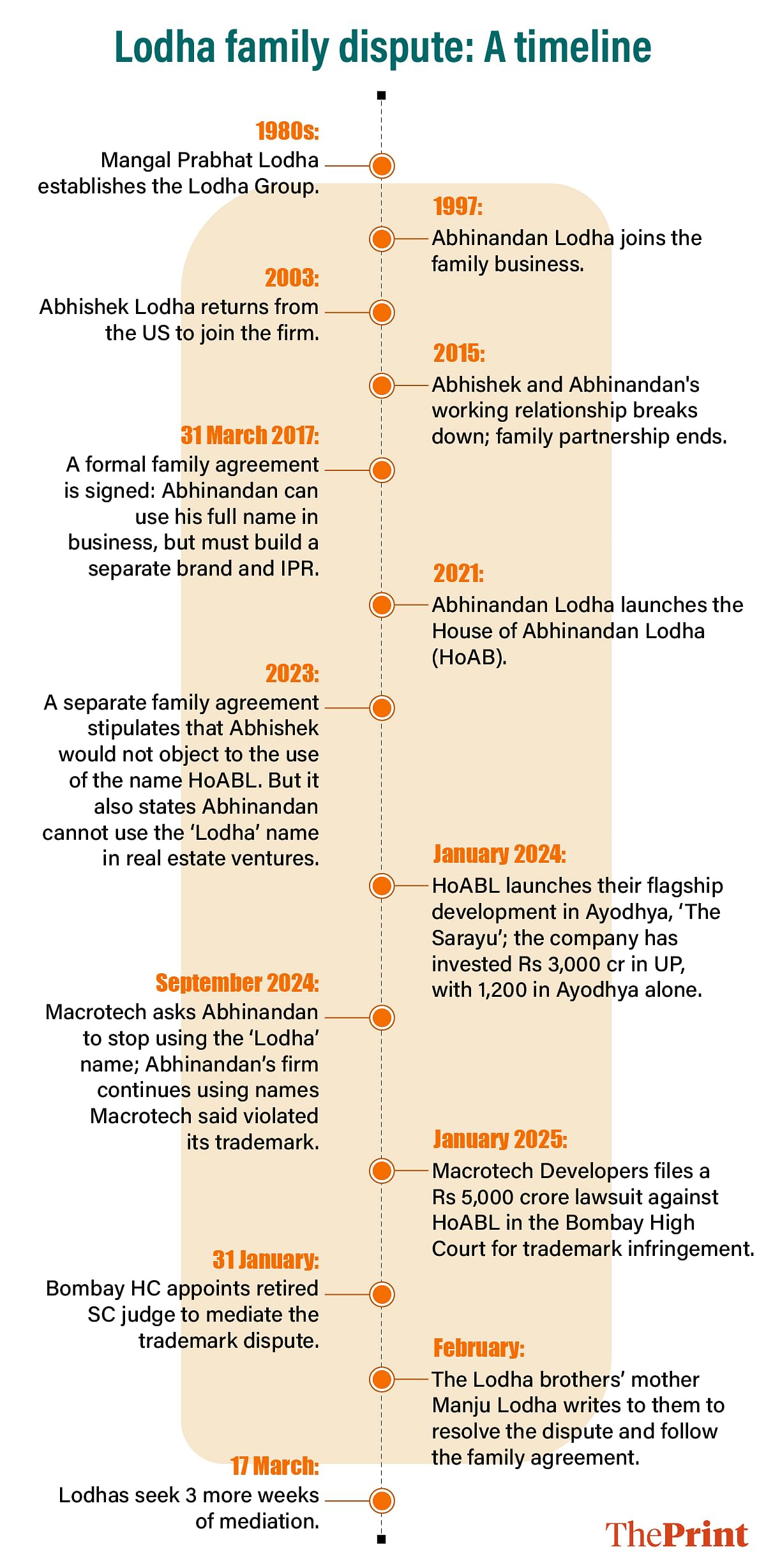

But younger son Abhinandan Lodha’s venture of legacy carving is in jeopardy. In January, Abhishek Lodha filed a Rs 5,000 crore trademark suit, accusing his younger brother of “deliberately misleading stakeholders” by positioning itself as part of the Lodha brand—not only resting on, but reaping rewards from the laurels of an empire that he did not build. Abhinandan denies the allegation.

When such a notice comes you only feel sad. The right, the wrong, the truth, the not-truth falls to the side. The courts will decide. But as an individual, I was saddened

-Abhinandan Lodha

Last week, Macrotech Developers also accused HoABL of forging the identity document and signature of its independent director, Ashwani Kumar, to register four companies using the name ‘Lodha’. HoABL has denied the allegation.

After the showdowns in the billionaire business houses of the Ambanis, Murugappas, Kalyanis, Modis, and Oberois, it’s the latest dynasty feud wrapped in corporate litigation.

While the scale is undeniably enormous, with Macrotech’s sales touching Rs 17,000 crore last year, experts say that at its core, this is a family dispute—and the companies are simply collateral.

But for both the Lodhas, this simmering tension isn’t about who owns which business. It’s over what can’t be divvied up or cut up into equal halves. Who owns a name is a more philosophical question.

In Indian real estate, surnames carry more weight than company logos. Brand names like Lodha, Oberoi, Godrej, Raheja, Hiranandani, and Piramal are industry shorthand for reputation, respect, and reliability.

Also Read: The real Bihar godfather is the land mafia. Fake receipts, muscle power, kangaroo courts

A house divided

About a year and a half ago, Abhishek Lodha told his younger brother to stop using the Lodha name. Prior to that, Abhinandan had been instructed to vacate his office in Lodha Excelus and hand it over to the parent company, Macrotech. He was paid Rs 25 crore for leaving the office, per a family agreement. They waited to file the suit, even though from a legal standpoint, it wasn’t ideal—because, as those privy to the feud put it, “they’re brothers at the end of the day.”

By that point, Abhinandan’s new life outside the family firm was well underway and his baby, the House of Abhinandan Lodha was coming into its own, expanding into 6 new cities.

Macrotech, meanwhile, was busy selling its most ambitious dream: Palava City. Branded not as a township but a “privately-owned city”, the 5,000-acre, Singapore-inspired development sits on the outskirts of Mumbai in Dombivli, complete with a company-curated culture and top-of-the-line infrastructure.

The two brothers might have drifted into different corners of the real estate world, but the Lodha name still binds them. And the IPR infringement claim weighs heavily.

In an interview with NDTV, Abhishek insisted this was a “trademark dispute, not a family dispute”. He pointed to another trademark clash, this one between Mahindra and Indigo. The carmaker was forced to rename its latest fleet of electric SUVs, originally called Mahindra 6E, owing to Indigo’s trademark of 6E.

“Indigo immediately objected, and Mahindra took a step back. It’s a very straightforward approach,” he said.

That case, however, involved companies in completely different industries. The Lodhas, in contrast, have always worked in the same universe.

Since steering Macrotech out of an onslaught of debt this year, Abhishek is staying in familiar waters.

“We’re quite focused on growth in the cities in which we’re operating. We hope to grow 3x in the next three years,” Abhishek told ThePrint over the phone. We’re following a low-risk model of operation, and the housing market is in a good place.”

An industry insider described Abhishek as “very intelligent, commercially savvy, and aggressive.” He referred to Abhinandan as a “newcomer”, dabbling in less complicated projects—plots of land rather than full-fledged developments.

“Newcomers usually sell plotted land. There’s a high risk in construction as more capital gets invested before delivery of the project,” he said. “For land, you just have to put in the basic infrastructure.”

But that’s a far cry from how Abhinandan is seen in his own offices. At Lodha Ventures, he cuts a larger-than-life figure. Staffers claim that he never sleeps, that he doesn’t own a smartphone, that he has a knack for putting people at ease. When he gives lectures—as he did recently in Nasik—tier-2 developers are reportedly “mesmerised” by how he conducts his business operations.

When he received news of his brother’s suit against him, he sent a text to one of his staffers. “Very sad today. Trying to settle down,” it reads.

Everything we stand for comes together in those five letters. Ultimately the brand is everything that a business stands for

-Abhishek Lodha

While discussing the dispute, he’s frank about his feelings while steering clear of the legal complications.

“When such a notice comes you only feel sad. The right, the wrong, the truth, the not-truth falls to the side,” he said. “The courts will decide. But as an individual, I was saddened.”

Behind him sits a framed photograph of his family—wife and two daughters—set against the backdrop of Imperial Goa, a HoABL project offering bungalow plots in Panjim.

Terms of separation

Abhishek and Abhinandan are the sons of BJP politician Mangal Prabhat Lodha, who founded the Lodha Group in the 1980s. Today, thousands of commercial and residential buildings across Mumbai carry the sleek, gold-rimmed ‘Lodha’ branding. The company’s beginnings, though, were relatively humble.

In 2003, when Abhishek returned from the US after a stint at McKinsey, Lodha’s sales were a paltry Rs 20–25 crore. There was no empire that needed minding. Instead, there was a foundation that needed to be built on—colossally. At this time, Abhinandan was already working at the Lodha group, having joined in 1997.

For over a decade, the two brothers worked side by side. But by 2015, their working relationship reached a breaking point. That year, their partnership ended due to a difference in values”. It was cemented through a family agreement in 2017, a copy of which has been accessed by ThePrint. It stated that Abhinandan’s new business could “advertise itself as an Abhinandan Lodha venture/project,” but had to “own and develop a distinct Intellectual Property Right (IPR)”.

Two years ago, another document clarified the terms further: Abhishek would not object to the use of the name House of Abhinandan Lodha. But there was a caveat—Abhinandan still could not use ‘Lodha Ventures’ nor lead with his last name.

This writ wasn’t quite followed. After leaving the family business, Abhinandan set up Lodha Ventures—an umbrella brand under which he launched several new companies. Other than the flagship HoABL, there’s Tomorrow Capital (a private equity fund), BeyondSkool (an upskilling platform), and the Sheetal Lodha Foundation.

Abhinandan’s pivot came at a time of seismic churn for the family business. By 2015, the Lodhas were staring at a Rs 20,000 crore debt, with fears that they were going to become “the next Unitech”. After a period of rapid expansion, they were now facing a huge backlog of incomplete projects.

A public fallout signals uncertainty about the business and can erode stakeholder trust in the family management’s capability to take the business forward

-Navneet Bhatnagar, IIM-Raipur professor

“The Lodhas went through various cash-flow mismatches. And you need cash to complete projects. Abhishek took a loan to pay off his old debt,” said a former employee of Piramal Fund Management, which invested Rs 2,320 crores in the Lodhas—at the time the biggest debt transaction in the real estate space.

Today, Lodha’s debts have reduced dramatically to a far more manageable Rs 4,320 crore.

“He executed the strategy to the tee. There wasn’t a single day’s delay,” the ex-Piramal employee added.

Banking on a name

In Romeo and Juliet, Shakespeare asked: what’s in a name? Four centuries later, that question became the subject of debate in the Bombay High Court. The dispute hinges on Abhinandan’s “continued use” of the Lodha name in his business.

“The genesis appears to be between two brothers—has any effort been made to sit down and resolve it?” judge Arif Doctor asked in a 27 January hearing.

But this isn’t just about two brothers squabbling. In Indian real estate, surnames carry more weight than company logos. Brand names like Lodha, Oberoi, Godrej, Raheja, Hiranandani, and Piramal are industry shorthand for reputation, respect, and reliability.

“Everything we stand for comes together in those five letters,” said Abhishek Lodha. “Ultimately the brand is everything that a business stands for. The name of the brand has nothing to do with the name of the company [Macrotech]. We also have every right to call ourselves Lodha developers.”

Confusion is what Abhishek Lodha wants to avoid. And going by the Macrotech petition, it’s already happening. It lists a slew of mix-ups, including one consumer notice where Abhishek was mistakenly referred to as CEO of Abhinandan’s company. In another case, a leading fashion designer excitedly told Abhishek that he’d bought a prime seaside plot after seeing Lodha hoardings in Alibag. But the project in question—Tomorrowland—belongs to HoABL.

In some sectors, these slip-ups might be shrugged off. But real estate is different. Names have to be guarded jealously because they are the value proposition. Trust matters when the product is worth crores.

“It’s extremely crucial to rely on a brand that has evolved over time. So many new developers come and fall by the wayside,” said Gulam Zia, executive director of Knight Frank, a global real estate consultancy firm. He gave the example of Unitech, once the country’s second largest developer, which never recovered after it left homebuyers in the lurch and trust in it collapsed.

Zia also pointed out that in India, it is generational developers who have maximum credibility. Even when plum brands like Gucci, Prada, and Trump tied up with homegrown builders, they failed at acquiring the kind of stature they enjoy globally.

“Lodha tied up with Trump and is not getting any value from it. Trump Towers in Delhi is non-existent,” he said. “Developers who’ve earned their brands should fight tooth and nail for them.”

While the Lodha Trump Towers in Mumbai’s Worli feature premium apartments and a show-house designed by Gauri Khan, and other projects are also coming up, global conglomerates have limited cache in India. There’s no image of a strong, united family at the helm. And for Indian consumers, that goes a long way.

A compelling business family story resonates with Indians. Dhirubhai Ambani’s tale—coming from a Gujarat village to taking his company public—is spun gold. Even allegations of market manipulation haven’t tarnished Reliance’s reputation, in part because of this story. Similarly, the Tatas have a strong brand narrative of being nation-builders.

“The family name helps build customer loyalty and competitive advantage, thereby contributing tangible monetary value to the business,” explained Navneet Bhatnagar, a professor of strategic management at IIM Raipur who researches family businesses.

When a public breakdown happens, that value gets tested, added Bhatnagar. This is especially true for multi-generational family businesses that project themselves as upholding certain values or belief systems. Public perception of the family and brand are inextricably linked.

“A public fallout signals uncertainty about the business and can erode stakeholder trust in the family management’s capability to take the business forward,” he said.

Meanwhile, for Abhinandan, it’s about charting his own legacy even if it draws power from his prestige-laden last name.

“The easiest thing for me would have been to start vertical real estate development in Mumbai. But then what? The brand value that Abhinandan Lodha has today—the uniqueness, the distinction, the fact that my consumer is participating with me for who I am has been a happy journey, though not easy,” he said.

“I saw the opportunity to create my own legacy and I took it.”

While the Lodhas have upped the ante on luxury towers, Abhinandan sells plots of land in emerging second-home destinations, and that too online, with the promise of transparency, airtight paperwork, and easy liquidity.

Luxury condos vs ‘Amazon of land’

Other than the smog, what’s visible from the verandah at Saint Amand, a members-only club on the top floor of the hyper-luxe Lodha World One, are more Lodha buildings—clean-cut and intimidating. They’re part of a select group of builders claiming the Mumbai skyline. It’s not just Antilia anymore.

Abhishek Lodha is credited with injecting his city with a version of luxury that’s blunt and unambiguous. Skyscrapers stretch as far as the eye can see. Condominiums that could rival those in Dubai—or, closer home, Gurugram. Offices that look like they’ve been ripped off a corporate vision board. It’s about power, aspiration, and insulation. The world outside no longer exists.

At Lodha World One, wide driveways loop around a cocoon of palm trees. The towers are packed together like sardines, but that’s the only giveaway of being in Mumbai –– where space is illusory and the crunch informs design.

The real estate market is essentially selling its customers the promise of a wellness-filled aspirational future—an imagined construction. Which is why trust becomes such a monumental provision.

“The product isn’t yet built, and you have to trust that they will build it. It’s a promise that’s being made,” said Anuj Puri, chairman of Anarock Property Consultants. “That’s why names resonate with consumers, especially in luxury and premium categories.”

While the Lodhas have upped the ante on luxury towers, Abhinandan is working with a different formula. He sells plots of land in emerging second-home destinations, and that too online, with the promise of transparency, airtight paperwork, and easy liquidity. HoABL refers to itself as the Amazon of land. About 20 percent of its buyers are NRIs, and 15 percent are celebrities.

“We’ve never met a single one of our 7,000 customers across the globe,” said Abhinandan. “We’re selling land virtually because that’s the level of trust HoABL has been able to build.”

The company hasn’t even crossed the five-year mark. But plotted land is considered a far less risky entry point than vertical construction.

“Newcomers sell plotted land. There’s a high risk in construction. You need things like quality finishings. For land, you just have to put in the infrastructure,” said the former DLF staffer quoted earlier.

However, Puri referred to HoABL as a first-of-its-kind venture.

“Nobody’s been able to institutionalise plotted sales like this,” he said. “Second is the way they’ve brought in price appreciation—more like a capital market review. And there’s the way they’ve leveraged technology. Usually it’s fragmented mom-and-pop guys who sell plotted land.”

What propels Abhinandan is the desire to carve out an identity that’s distinct from that of his family. It’s a tricky balance. He has to prove he is different and yet not let go of the Lodha legacy pie.

“There was no way I was going to become a smaller version of somebody,” he said. “This is why, despite having lived in Mumbai all my life, I took the conscious decision to go to places that I never would even have gone to on holiday.”

Mediation—legal and maternal

It’s often the mother who plays peacemaker when a corporate battle threatens to fracture the family. When the Ambani brothers fell out, it was Kokilaben who played mediator. In the Lodha family, that role has fallen to Manju Mangal Prabhat Lodha.

Despite gravitating to different segments of the real estate industry, Abhishek and Abhinandan have plenty in common. Both live in buildings that bear the Lodha name. Both have similar boyish features, spend downtime with their children, and—according to their mother—fall ill at the same time. They’re also, of course, set to inherit chunks of the same empire.

In a letter dated 21 February, parts of which found its way into newspapers and online portals, Manju Lodha delivered a heartfelt plea to her sons to end their feud.

“Whatever I own I will definitely leave behind for both of you. I pray that both you bring an end to your dispute and focus your energy on growing your respective businesses and taking care of your family,” are her parting lines.

She described their bond as akin to Ram and Lakshman, and said her friends wished they had sons like hers. But beneath the emotion, the message was firm.

“The final arrangement within our family was documented in our amended family agreement dated 31st March 2017. We confirm that both of you have no right of any form in the other brother’s business or assets or shareholdings,” she wrote.

The letter came with a list of directives, including: you will not say anything wrong about ach other, you will not fight with each other, You will not interfere in any manner in each other’s business.

While the case pits brother against brother, there are really six stakeholders—both parents, both sons, and both companies.

On 31 January, after both brothers agreed to mediation, the Bombay High Court appointed retired Supreme Court judge RV Raveendran to resolve the dispute in five weeks, noting that “hopefully, it will be solved and not end in 20 years of fighting.”

The process is private and confidential, but no resolution has been reached yet. On 17 March, the Lodhas sought three more weeks of mediation.

Personal grudges, public disputes

India has 191 billionaires, the third-highest number in the world after China and the US. It’s no surprise, then, that the country is also home to a fair share of high-stakes public spats. The Lodhas are far from the only brothers to go head-to-head in court.

Family disputes in Indian business circles tend to follow familiar patterns, according to IIM’s Bhatnagar. At the core are personal grievances and power imbalances—with courts left to enforce what began as family agreements.

“Often, in the Indian context, problems are brushed under the rug and not actively dealt with at the initial stage. Eventually they get amplified over time and emerge later as a bigger dispute that is even more difficult to resolve,” he said. “Family and business systems are like conjoined twins. A problem in one quickly affects the other. Personal grievances turn into professional conflicts.”

The Ambanis are the most well-known example. At its peak, a friend of the family described the rift as “a Shakespearean tragedy”, adding that there was no conversation or warmth between the brothers.

“Sometimes they are forced to shake hands, but they do not look at each other,” said the friend of that time. Things seem to have thawed since then, but barely.

Unlike the Ambanis’ case, where Dhirubhai left no will, the Lodhas at least have a family agreement in place. Their businesses already entirely separate entities, and terms were formally laid out in 2017.

But family agreements aren’t always enough. Sunanda Hiremath, sister of manufacturing magnate Baba Kalyani, is currently in court over an unfulfilled family agreement dating back to the 1990s.

Despite being in the throes of a massive spat, Hiremath and her husband Jai emphasised the importance of ‘family-unity’. They also thanked their stars—at least their businesses run under separate names.

“It would’ve become a problem. That’s why ours is totally different. There’s no conflict here,” said Jai told ThePrint.

In real estate, a handful of families dominate, and several have had rifts. Before Lodha vs Lodha, there was Raheja vs Raheja and Godrej vs Godrej.

There are now multiple Rahejas and multiple Godrejs operating highly diversified businesses. Yet, according to Bhatnagar, market confusion persists.

To circumvent this, brand strategy is essential. The businesses use dramatically different logos and other methods to signal their distinct identity. When the Ambanis split, for instance, Anil’s ADAG group adopted a different logo and identity.

In the case of the Lodhas, Macrotech’s logo spells out the family name in spaced-out golden letters. Lodha Ventures uses stylised initials, with one half resembling a building block.

“While a shared family name can initially capitalise on legacy, effective brand differentiation and strategic sector separation become paramount to preempt confusion and potential conflicts as family businesses grow and diversify,” Bhatnagar said.

In real estate, a handful of families dominate, and several have had rifts. Before Lodha vs Lodha, there was Raheja vs Raheja and Godrej vs Godrej.

Also Read: Gurugram has a giant illegal guest-house problem. Over 4,000 notices, yet business as usual

A legacy in land—and politics

Mangal Prabhat Lodha wanted to immerse himself in a life of “public service”, so he left the business to his sons. He’s no longer involved at all. The company is now backed by “some of the world’s biggest investors”, including Wellington and Ivanhoe Cambridge. Abhishek holds the reins.

The office of the Lodha Foundation—the company’s charitable arm—in Breach Candy, where a hoarding outside claims Mangal Prabhat is “available every single day” but was empty at the time of ThePrint’s visit last month. The hall inside is austere and pokey, with haphazardly placed chairs and framed photographs of RSS ideologues VD Savarkar and MS Golwalkar. Lodha was an active member of the ABVP, the student wing of the RSS, before he joined the BJP.

Hanging on the balcony is the tagline: Lodha Foundation, A Better Life.

Real estate in India is often perceived as a ‘dirty’ business. Corruption, cronyism, and political nexuses are rampant. But according to Prasad Lad, vice president of the BJP’s Maharashtra unit, Mangal Prabhat has largely steered clear of the this convention.

“He’s managed his politics very differently. He never mixed his politics with business, nor his business with politics. We’ve seen the Lodha group from scratch and feel proud when we see them doing premium projects,” said Lad.

He also pointed out that Lodha has played a key role in advancing RSS and Hindutva work in the state.

While the Lodha Group began with Mangal Prabhat, the family legacy starts with Guman Mal Lodha, grandfather of Abhishek and Abhinandan. A lawyer who rose to become Chief Justice of the Guwahati High Court, he was a classic rags-to-riches figure, Abhishek said in an interview with Forbes. He studied by candlelight in his village and made his way up the ladder against all odds.

Even today, his influence endures. According to Abhinandan, Guman Mal had worked with current UP Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath in the 1990s—connections that proved useful when HoABL entered Ayodhya and set about acquiring land for The Sarayu.

“When Yogi Adityanath came to know I’m the grandson of Guman Mal Lodhaji, he was even more affectionate towards me, as they were both part of the Ramjanmabhoomi movement. He understood my interest,” he said. “I’ve definitely benefited from that legacy.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)