Books

Saddled Histories: David Chaffetz on the Rise and Ruin of the Horse Empire

David Chaffetz is an independent scholar and writer whose work bridges traditional scholarship and modern interpretation, offering fresh perspectives on the cultural and geopolitical forces that have shaped Asia. A graduate of Harvard University, where he studied under renowned Inner Asia specialists Richard Frye and Joseph Fletcher, and later a student of Edward Allworth at Columbia, Chaffetz has spent more than four decades immersed in the study of Middle Eastern and Inner Asian history.

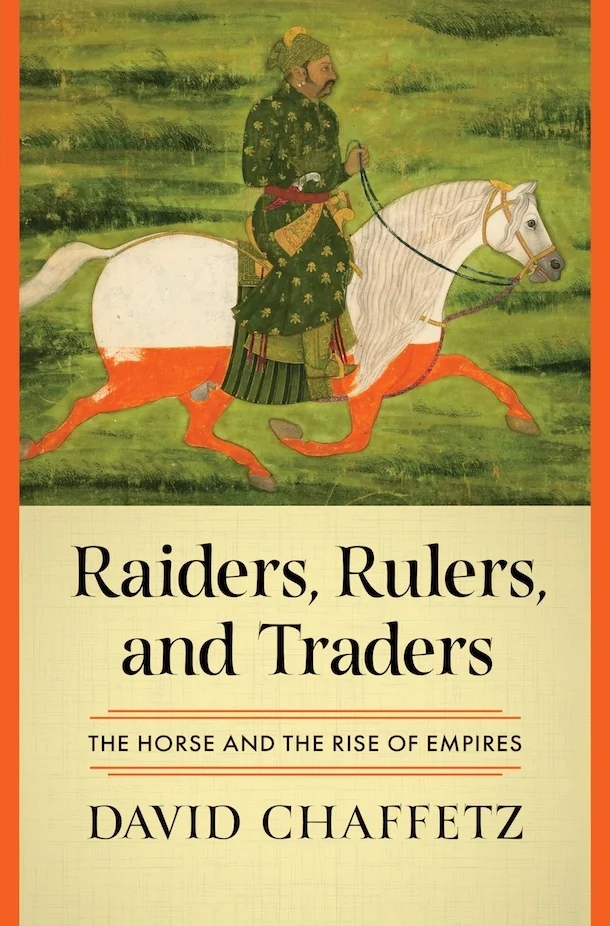

His landmark 1981 travelogue, A Journey through Afghanistan, praised by Owen Lattimore and republished several times, launched a literary and scholarly career focused on the overlooked narratives of Asia. His recent works, including Three Asian Divas and Raiders, Rulers, and Traders: The Horse and the Rise of Empires, examine the vital roles played by women, trade, and equine culture in transmitting and transforming Asian civilization.

Chaffetz has traveled extensively through Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, China, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, and Russia, conducting research in over ten languages, including Persian, Turkish, and Russian. A regular contributor to the Asian Review of Books, he has also written for the South China Morning Post and the Nikkei Asian Review. He is a member of the Royal Society for Asian Affairs, the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, the Explorers Club, and Lisbon’s Gremio Literario. He currently divides his time between Lisbon and Paris.

Scott Douglas Jacobsen: I’d like to start with something unexpected: What does fermented mare’s milk taste like in Mongolia?

Scott Douglas Jacobsen: I’d like to start with something unexpected: What does fermented mare’s milk taste like in Mongolia?

David Chaffetz: Initially, it tastes rather good. Let’s say the attack, as a wine taster might say, is very refreshing. The problem is that it has an aftertaste of urine. So, if you keep drinking it—and that’s the idea—you always enjoy it. But the minute you stop, you want to rinse your mouth with water, which is unavailable.

Jacobsen: Regarding your latest book, Raiders, Rulers, and Traders, what initially inspired your focus on horses’ role in shaping empires and global trade networks?

Chaffetz: A long time ago, I read a book that was very influential in the 1960s and 1970s called The Rise of the West by William McNeill at the University of Chicago. He was one of the first scholars to address a popular audience about the amazing interactions across the Eurasian continent—between China, India, the Middle East, and Europe. Before that, people didn’t talk much about what China, for example, owed to the West or to India, what India owed West, or what the debt of the West to China and India.

He had these maps showing gear wheels—bold, graphic gear wheels—connecting all the countries. But these graphics left the obvious question unanswered: How did such a gearbox function? In other words, how did these far-flung civilizations communicate with one another and connect? And above all, why did they need to communicate and connect? That issue has been on my mind for more than 50 years.

Through extensive travel in Asia, I observed that most countries have very prominent horse cultures. The horse seems to play an important role in the arts, sports, and social status—at least traditional social status. Today, if you talk about the horse as a social status symbol in China, you’re talking about the nouveau riche who play polo. Traditionally, the horse was an extremely important marker of social place in China, as reflected in the arts.

I realized that William McNeill’s gearbox, which connected Asian civilizations with Europe, was made up of horses. The horse was not only the mechanism for connecting civilizations—it was also one of the primary reasons those civilizations did business with one another. The peripheral countries around the Eurasian continent were poor in horses. The center of Eurasia—Inner Asia and Central Asia—was rich in horses. That gave rise to a trading system connecting the Eurasian continent and making it a kind of global civilization for centuries.

Jacobsen: How far back does the evolution of horse domestication go?

Chaffetz: So, it’s a very gradual process. One of the fascinating things is that it’s so gradual, but we can see so many steps that we can imagine, century by century, people making these huge leaps forward in technology and best practices.

There’s a long-standing debate as to whether we’re talking about domestication occurring around 5,000 BC or around 3,000 BC. The current state of the play says that hunters in Central Asia—Kazakhstan or Southern Russia—possibly domesticated a breed of horses 5,000 years ago, moving from butchering them to herding them. But then those horses and those people died out, without successors. Then, another attempt to domesticate horses started 3,000 years ago, which was more successful. Those horses are the unique ancestors of all our domesticated horses today.

I like the later start date because we don’t see people riding into history—literally riding into history—until about 2,000 BC. So, if horses had been domesticated in 5,000 BC, what the hell were they doing for 2,000 or 3,000 years that no one saw them show up? It just seems improbable to me.

Anyway, so they’re domesticated in the sense that we begin to herd them as livestock, interfering with their reproduction, culling animals that don’t give much milk, culling males that are too aggressive, and winding up with mares that give a lot of milk and stallions which are not so wild and don’t run off with the mares.

To herd those animals, we have to ride them because they can run much faster than humans—unlike sheep, cows, and goats. So inevitably, we have to ride them. We begin moving with them over fairly considerable distances. We get better at riding.

At some point, we adopt them for pulling carts—fast little carts—probably originally for racing, around 2,000 BC. A couple of hundred years after that—so now 1,800 BC—chariot riding has become quite a thing, also for racing, prestige, but inevitably for warfare. This more or less coincides with the Bronze Age heroes of Homer’s Iliad—Hector and Achilles—who show up at the battlefield on chariots.

Chariots are mentioned very frequently in the Bible. Next week is the Jewish Passover. The Pharaoh chased the children of Israel towards the Red Sea with an army of chariots, probably around 1,800 or 1,600 BC. So, chariots were the horses’ entry into warfare.

To follow up on that—by 1,000 BC, so after about 800 years of chariot warfare, people figured out that it was much more efficient, cheaper, and potentially more lethal to fight on the horse itself rather than from a cart—riding the horse and either slinging javelins or using a bow and arrow. Eventually, mounted archers—mounted cavalry—replaced chariots, starting around 1,000 BC in the Middle East and about 500 BC in China.

Jacobsen: Even in the relatively recent history of show jumping—which I’ve covered in Canada as part of my previous journalistic work—we see stark generational shifts in how the sport approaches safety. Riders like Ian Millar, Eric Lamaze, Gail Greenough, Beth Underhill, Michel Vaillancourt, and Jim Day came up in an era very different from that of today’s leaders such as Tiffany Foster and Erynn Ballard. Over time, the sport has introduced safety mandates: chinstraps, vests, breakaway cups on jumps, and obstacle courses built with fiberglass or PVC. These changes reflect a broader effort to make the sport safer and more regulated.

This signals a kind of domestication—not unlike the transition from chariot warfare to riding astride in saddles, whether soft or rigid. It feels like part of a long arc of human-equine evolution. In that context, I’m curious: Across this several-thousand-year trajectory of domestication and equestrian training, were there ever periods where knowledge was lost—moments when the transmission of skills or traditions faltered before later being revived?

Chaffetz: That’s an interesting question. The way of life of the people who live by horse breeding—the Turco-Mongolian population of Central Asia and Inner Asia—has been stable for over 3,000 years.

Since the emergence of riding horseback to fight, up until the beginning of the 20th century, their way of life has been extremely stable. Improvements in tack, riding technique, and horse evolution have only made horses bigger, stronger, and better.

Their horses improved naturally because they were not bred to have pure bloodlines. They were bred when a stallion was deemed a very good stallion, and everyone wanted to use that stallion to breed with their mares. They didn’t have a stud book. They didn’t have rules about who should be bred with whom.

So, I think they probably had the toughest, best, and most powerful horses for many years.

In the 20th century, totalitarian governments were politically opposed to horse breeders in all those countries.These governments suppressed the horse breeders’ way of life, resulting in a huge loss of knowledge about how to breed and train horses, which they’re currently trying to recover from.

For example, the Nomad Games in Central Asia are gaining in popularity. Here countries that have a tradition of these mounted games—like the famous buzkashi or kukpar, where riders pick a heavy animal carcass off the ground—I call it rugby on horseback—or polo, or racing, or mounted archery, compete for prizes. People come from all over the world to see and compete in them. They’re reconstructing the equine knowledge base of the Central Asians, who had it for 3,000 years and almost lost it completely in the 20th century.

I don’t know much about Western riding traditions. Still, my feeling is that there has been so much money in it for so many years—betting on horses in the Anglosphere: UK, Ireland, Canada, the U.S., Australia—that it would be very surprising to me if, in the past 300 or 400 years, we’ve lost any knowledge along the way.

But I would mention that in the West our horses are dangerously overbred and unhealthy, and somebody will have to do something about this—or we will be in big trouble with our horses.

Jacobsen: Can you explain the dual role that horses have historically played—as both currency and commodity—and what that tells us about their place in the broader economic and cultural systems of the societies that relied on them?

Chaffetz: Well, the advantage of horses as a trade item is that they feed themselves and walk themselves. If you’re trying to make money over a very large distance—let’s say you’re in the middle of Asia—there’s not much opportunity to make money, but you have a huge herd of horses. You can ride those horses into India; you can ride them to China; you can ride them to Moscow and sell them for big money. In our terms, let’s say currency—$500 to $1,000 per head. Even today, for a Central Asian, $1,000 is a lot of money. So, the horse is the ideal tradable commodity.

It’s also potentially a prestige commodity, depending on how good the horse is. There are always exceptional horses that fetch prices equivalent to what we would pay today for a Lamborghini or a Ferrari. Those horses were often, in fact, given as gifts to emperors of the different countries of Asia as a commercial sweetener to open the door for commercial relationships. We have many paintings or sculptures of these prestigious horses in Chinese, Indian, or Iranian art sent as gifts to rulers. That underscores the importance of the horse as a trading commodity.

Jacobsen: In most civilizations—particularly in their early stages of development—humans tend to self-mythologize, often envisioning their gods in anthropomorphic terms. Similarly, we see the emergence of equine myths like Pegasus or the unicorn. How have horses been mythologized across art, literature, and ritual? And how does that equine symbolism shape, or become woven into, the self-narrative of empires throughout history?

Chaffetz: Let’s discuss the archaeological record. Starting around 2000 BC, we begin to find elaborate—multi-level graves—containing elite individuals: a man and a woman or several members of a family, together with other people, presumably sacrificed servants or retainers, and significantly sacrificed horses.

We also know from the rituals embedded in the sacred scriptures of the ancient Indians and Iranians that they held horse races in honor of the dead and then sacrificed the horses following the race.

I recall that in Homer’s Iliad, when Priam buries Hector, he orders horse races to be performed in honour of his son. So, the horse race can be seen as a symbol of the journey of the soul of the dead into the other world. The sacrificed horse performs the same role he performed for the departed in life.

This is very pervasive and persistent across Eurasia. Until the Tang Dynasty in China—so we’re talking 900 AD—we saw extensive grave gifts in terra-cotta horses—images of horses superseding horse sacrifices.

Horses have always been viewed as partly from another world, suitable for accompanying us on our journey into that world. That’s one of the most important symbolic uses of horses in our cultures.

There are many others: the horse can metaphorize the human soul. In both Plato’s dialogues and Buddhist scripture, the horse represents the soul—fleeing madly forward, not knowing where it’s going, in a panic. It’s up to the sentient soul—the superego, in Freudian terms—to control that frightened horse and make sure it goes in the right direction.

So, there’s also a psychological aspect to how we view horses.

Finally, because horses are very beautiful and associated with power and prestige, we have aestheticized them—their bodies, their speed, their colours. They are a major subject of the visual arts in Chinese sculpture, painting, and in Iranian and Mughal painting. And, of course, in the Anglo world again, there are all those beautiful paintings of racehorses. And we have Rosa Bonheur, the celebrated French painter of horses. Horses are almost universally admired and approved as aesthetic objects.

Those are the three main roles horses play in the symbolic world.

Jacobsen: At the dawn of the 20th century, entire industries revolved around the industrial-scale cleanup of horse manure in major cities—an unglamorous but central part of urban life. That world has vanished. Today, horses have become rare, even precious, commodities. As you pointed out, some elite horses are now valued at $500,000. I’ve learned from my conversations with experts that a single entry-level Olympic horse often starts at $500,000—or €500,000—and the average can soar to €5 million. And that’s just one. Riders frequently need seven or eight, as the horses tire easily and often specialize in different types of course design.

These animals are bred with extreme precision—for traits like “scopiness”—and their value has skyrocketed. Do you see a curious continuity between this elite modern equestrian culture and ancient traditions in which horses were reserved for rulers, royal burials, or ceremonial contests? In a way, are we witnessing a kind of exaggerated return to those aristocratic norms, where billionaires have reignited a high-stakes interest in horses, driving prices through the roof? Meanwhile, at the other end of the spectrum, practical horse breeding and riding for everyday use—ranch work and rural life—has largely faded from the mainstream.

Chaffetz: Yes, there’s a bifurcation in the world of horses. But bifurcation has always existed. In the past, there were ordinary work horses and elite horses. In the past, ordinary horses could easily be raised in countries where horses could graze year-round outside—without stables or foddering— so the cost of keeping a horse was within everyone’s reach. This would be typical of Afghanistan as well as Texas today. But this phenomenon of was much more widespread in the past. As the world becomes more urbanized, and as we put more land under plow, the availability of land where horses can feed themselves is reduced.

You now have to spend serious money if you’re going to stable an animal, feed it, or have someone else look after it. Very few people will work as stable boys or stable girls, and there is a significant shortage of veterinarians. For all these reasons, the average person cannot keep a horse at any reasonable cost as they could have 50 or 70 years ago in rural British Columbia or Upstate New York. Today, they have to commit substantial money to raising that horse.

So that’s the fate of, let’s call it, the everyday horse.

On the high end, nothing has changed in a thousand years. Elite horses have always been pampered. They’ve always had grooms. They’ve always had special fodder. In my book, I describe the efforts that Chinese or Mughal emperors in India undertook to care for their horses. They were the Olympic competition horses, the Kentucky Derby horses of their time. They were priceless.

One of the Mughal emperors gave one of these horses to his brother-in-law, the Maharaja of Jaipur. The emperor wrote that the Maharaja was “so happy receiving the horse that it was as if I had given him a whole kingdom.” So, you can see that the $5 million horse existed 500 years ago. The billionaires today continue this time-honored tradition of maharajas and kings who had these incredible horses.

Again, we should keep in mind that, in football/soccer, for example, players like Kylian Mbappé or Cristiano Ronaldo command salaries many times higher than the average professional. Similarly, average horses are worth far less than the greatest horses. This kind of bifurcation is true in every sport.

Jacobsen: What thread runs through Mongolia, Persia, and India regarding how they have viewed horses over the millennia?

Chaffetz: These are countries where, traditionally, nobody with self-respect would ever walk. They rode everywhere. This is very evident in Persian paintings: you see scenes where the king is sitting in a garden, surrounded by his courtiers and enjoying himself. There are musicians, dancing girls, food, and wine. But always, you see a horse posted close to the king because the minute he’s done with his picnic or court session, he will walk two yards, leap up on the horse, and ride off.

They couldn’t imagine going anywhere on foot. When you rode into their palaces—in many of these buildings, for example, the Forbidden City in Beijing—horse ramps led into the inner pavilion because the emperor would have ridden in, left the horse at the very threshold of his residence, and dismounted only at that point.

So, it’s a completely horse-focused society.

And that, as I said, was one of those common elements that made me think those countries were connected via the horse.

I’d also like to point out that the old Russian state—before Peter the Great, before the modernization and Europeanization of Russia—looked and felt very much like Mongolia or Iran in the way people rode, raised horses, and dressed and in the importance of the horse trade for the Muscovite State at the time.

Jacobsen: What are you hoping people take away from Raiders, Rulers, and Traders?

Chaffetz: The horse is this phenomenon that had been so important for—as I say—3,000 years, since we started riding horses for warfare, until the beginning of the 20th century. The horse drove a way of life. It determined the destiny of empires that accounted for half of the world’s population at the time. It shaped a whole culture of horsemanship and riding.

Then, at the beginning of the 20th century—as you pointed out—suddenly, horses were no longer important except in the very limited forms of showing and racing. They lose their significance from an economic, political, and military perspective. It happened very quickly. The horse breeders disappeared from history.

I think what you take away is that a way of life can develop and be extremely persistent and robust for three millennia and then disappear in one man’s lifetime. This makes us think that, while our lifestyles appear to be stable and persistent, what will happen in our lifetime or the next generation when a major technological change comes along, and elements of our world that we took for granted become irrelevant. I want people to think about that sense of loss and change.

Jacobsen: David, thank you for the opportunity and your time today. I appreciate your time and expertise. It was nice to meet you.

Chaffetz: Nice, my pleasure, Scott. It was good talking to you, too. Bye-bye.