SENTENCED TO THE SIDEWALK: One woman’s misery reveals flaws in Oregon commitments

Melinda Lou Kayser died in plain view on a cold night 11 weeks after Marion County investigators determined she could take care of herself.

Kayser, 62, could barely move because of a broken hip that healed wrong.

She didn’t feed herself for months.

She passed her days and nights laying down, often naked, on cold Salem sidewalks surrounded by trash and covered in her own feces.

Her frustration and confusion at her situation led to her attacking others and being hurt herself.

Police, her daughter and advocates who visited her over months could clearly see that she was profoundly mentally ill and wasting away as a result.

Yet after visiting her on the sidewalk, a team of Marion County investigators determined she didn’t qualify to be forced into mental health treatment.

A five-month Salem Reporter investigation found that Kayser’s death was the inevitable conclusion of a statewide mental health system forged under the idea that if someone is rejecting help, it’s in their best interest to be left on the street.

Her tormented life and public death reveal opportunities missed and forbidden under Oregon law, which has made forcing people into psychiatric treatment nearly impossible unless they’re about to kill themselves or someone else.

Decades of inaction and missteps by politicians and the Oregon Health Authority leave few options outside of the criminal justice system for people who desperately need help. Instead, the state’s system delivers people like Kayser to sidewalks and ensures they can only leave in the back of a police car, an ambulance or a body bag.

The state designed a process, called civil commitment, as a lifeline to compel mental health treatment for people whose symptoms lead to serious violence against themselves or others. That includes those who cannot meet their own basic needs of shelter, food, water and health care. The process assumes that if the person was lucid, they would want such help.

On paper, the law allows concerned relatives to petition a judge with evidence that someone cannot care for themselves. But obtuse laws followed by years of narrow interpretation mean the vast majority of such petitions are rejected before going to trial, Salem Reporter found.

Forcing medication and institutionalization is an unpalatable response to someone in crisis. It’s a last resort that feels too close to a century of abuse inside state hospitals, which stole lifetimes from disabled and poor people.

In its refusal to face ambiguity or adequately fund alternative care, Oregon’s advocates and lawmakers have replaced that abuse with neglect, especially for unsheltered people.

The result is that civil commitment, intended as a last resort, is now the only resort, and those who need it most are barred from it under the guise of protecting their rights.

Blocked from resources

Police and county records show Kayser’s dire condition in the last years of her life, along with videos, notes and photographs taken by her daughter, Jessica Finnegan. They trace four decades of escalating mental health problems and life on the streets.

A video taken last August shows Kayser naked, sitting on the corner of Southeast Lancaster Drive and Rickey Street in Salem, right in front of McDonald’s. She’s surrounded by clothes and trash: a box of cereal, empty McDonald’s bags, a carton of milk warming in the summer sun.

“Mom,” Finnegan says from behind the camera, her voice calm and exhausted.

“What,” Kayser responds, an angry, low croak. She clutches a burger in one hand and holds an unzipped sweatshirt over her chest with the other.

Kayser glares at the camera, working her jaw. She’s 61, but looks much older. Drivers enter and exit the nearby drive-thru behind her, and cars roar past them on the street.

“How come you’re out here with no shirt on?” Finnegan says. “You’re completely naked. How come?”

Finnegan, later showing the video from her phone to a reporter, pointed at her mother’s bare arms. “I was trying to get her arms, she’s got blood all up and down her arms. From scratching.”

Finnegan recorded the video to support a petition that she submitted to Marion County on Aug. 26, asking that her mother be committed against her will to psychiatric care. She had read the state law, which states that if someone can’t take care of themselves, they’re eligible for treatment.

Kayser could barely walk and did not take care of her feet, risking amputation. She relied on her daughter, advocates, or strangers to bring her food, but yelled at those helping her. Sometimes, she threw things.

Jimmy Jones, who leads much of the region’s homeless sheltering and support services as the executive director of the Mid-Willamette Valley Community Action Agency, said that it’s a situation he’s seen over and over again: people with severe mental illnesses slowly deteriorating in plain public view because of a system that leaves them no other options.

Jones said not many people like Kayser are living on Salem’s streets — fewer than 10 at any given time. They have extreme mental health problems which put them at risk of a slow death from frostbite or sepsis. He said up to 50 people in Salem are on the threshold of such a condition, able to go to a shelter on a cold night but still in need of help to manage care for themselves.

Until they reach the brink of death — slipping into unconsciousness, overdosing or bleeding profusely — social service workers either hand them a business card they aren’t able to respond to, or a meal to get them to the next day.

Jones said he has never seen an unsheltered person such as Kayser get committed to long-term psychiatric treatment as a result.

“I think it would be incredibly rare for any general street homeless person to find their way into that system. It’s just not a resource we can take seriously as an option,” Jones said.

He recalled the worst case he has ever seen: a Salem woman who was never lucid, and who was subject to shocking violence and repeated sexual assaults while living on the street as a result. She’d step into traffic. She’d snatch people’s pets from her spot on the sidewalk. And yet, court investigators and judges decided she, too, could take care of herself and wasn’t eligible for commitment.

Most people in Kayser’s situation have no champion. They’ve lost contact with any family, often driving them away with their behavior.

Kayser was different.

Her daughter was there for her.

Despite a traumatic childhood and extended separations, Finnegan reconnected with her mom and tried for years to find her housing, convince her to accept help and ultimately petitioned to force her to accept treatment.

Her efforts weren’t enough to save her mother.

A traumatic life

Kayser was born in Amarillo, Texas, in 1962. She had five siblings.

Finnegan said she and her mother rarely talked about her childhood, but her recollections and those of Kayser’s older sister Rose combined with records from Kayser’s life paint a picture of dysfunction and challenges spanning decades. Rose asked to only be identified by first name for privacy.

Kayser’s mother was a dietitian and her father was a Korean War veteran who laid carpets for a living. She and her dad were close and often fished for catfish at the river together. Kayser held a special place in their dad’s heart as the youngest child, Rose said.

Kayser told an Oregon State Hospital interviewer in 1997 that at 9, she smoked her first cigarette. At 12, she started drinking and using drugs. Rose, six years her senior, said she didn’t believe that could be true, because she would have seen it or someone in their small community would have told her.

Some of the other information Kayser gave in the 1997 interview proved incorrect, including the number of siblings she had, according to her sister.

Kayser dropped out of school as a freshman, and later earned her GED, according to the state hospital interview.

As a young adult, Kayser worked odd jobs including as a kitchen assistant. Kayser said she had a history of anxiety attacks, and was diagnosed with “a manic depression condition” she treated with medication. She gave birth to Finnegan, her first of two daughters, at age 19. She told the interviewer she started using meth at 21.

“When I was a teenager, I was waiting for the call to find out that she was dead in a ditch somewhere.”

Jessica Finnegan, on her mother Melinda Lou Kayser

Kayser was a great person when her mental health and addictions were managed, Rose said. She always volunteered to babysit her nieces and nephews and enjoyed helping around the house.

Both of Kayser’s parents died before she was 30. Kayser blamed herself for her father’s death, having delayed her trip home by stopping to buy marijuana. When she returned, she found his body. It was a complication from a spinal cord injury, Rose said, and there was nothing Kayser could have done if she had been there.

But his death triggered Kayser’s first psychotic episode. She disappeared. The family found her a few days later at the hospital, believing she was speaking to him in the hospital room, Rose said.

She was never the same.

As her mental health deteriorated, domestic violence brought police to Kayser multiple times throughout the 1990s, when she was living in Roseburg.

Finnegan recalled that around that time Kayser dove off a loft onto the floor of a concrete garage running from visions of demons.

“It was just always chaotic. So I think I was just used to, and had built walls up from a young age. When I was a teenager, I was waiting for the call to find out that she was dead in a ditch somewhere,” Finnegan said.

Despite being chronically homeless, on one of Finnegan’s birthdays, Kayser bought her daughter a blue top from Maurices, using a credit card she somehow managed to get.

“They had nice clothes there,” Finnegan said. There was a time in her childhood when she’d only had two shirts for school.

Her mom also interjected to defend Finnegan during household fights, not allowing her partners to speak to her daughter aggressively.

“So that’s how I knew that she loved me. I could see effort. She would try to do the right things,” Finnegan said.

Kayser wanted to get better. She sought mental health treatment at age 33, in 1996, according to county records. She went to the hospital in Roseburg herself and asked to be committed.

The hospital turned her away. Available records don’t say why.

A few days later, she fought her husband in a convenience store parking lot, a fresh bruise already on her eye. When police arrived, she begged them to take her to the mental hospital. Responding officers arrested her for having meth and assaulting her husband.

It wasn’t until Kayser stabbed a man a year later that Oregon’s mental health system allowed her to get help.

The attack took place in a house next to a sports bar that Kayser shared with a man.

The roommate told police that he had been sitting on the couch when Kayser kicked the door open. When he saw she held a knife, he said he threw a pillow from the couch at her to stop her advance. It made her more upset.

Police responded and arrested Kayser.

“(Victim) said he did not know why Kayser was acting so ‘crazy’ but he felt it was because she’d been on meth for awhile and drinking,” the police report said

In a letter to the judge from jail, Kayser admitted growing agitated and said she felt smothered. Her husband used to smother her, she wrote.

She told the judge she worried she would lose her housing because of the arrest.

That March, Kayser’s attorney submitted a request to have her committed at the Oregon State Hospital, saying she was not mentally well enough to defend herself in court. It’s a status called “aid and assist,” which now accounts for the vast majority of patients in the state hospital.

While that was being processed, Kayser wrote letters to the judge from jail asking for mental health treatment.

“At the end of last summer my daughter made a phone call to 911 and asked for mental health aid and I was shipped to jail,” she wrote.

In April 1997, a psychologist interviewed Kayser for four hours at the Oregon State Hospital. According to their records, she’d been in contact with county social services nine times in two years before getting to that point.

“Her speech had a somewhat pressured quality to it and she diverged from the topic at hand very easily,” the report said, which described her eye contact as intense.

Kayser denied being suicidal or wanting to harm others. She said she saw spirits occasionally.

She refused to finish the psychological evaluation, and instead laid on the floor and wept.

The evaluator said she likely had bipolar disorder, paired with a history of substance use. Due to her symptoms, the evaluator determined she would not be able to aid and assist in her own defense, but could be stabilized to do so through medication. She was committed to the state hospital.

In May, Kayser wrote the judge from the hospital.

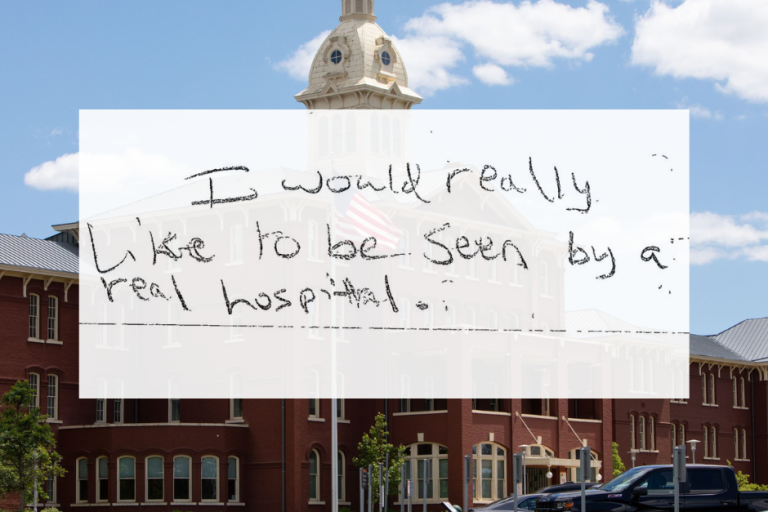

“I finally got my meds and am doing and feeling much better,” Kayser wrote about a month after she reached the hospital. “I sure wish someone would do something please. I would really like to be able to see my family and start a new life.”

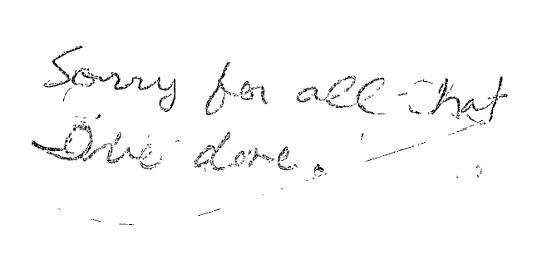

On the envelope, she wrote, “Sorry for all that I’ve done.”

The state treatment served its purpose. She was judged fit to face her criminal charge. She pleaded no contest on May 30, 1997, and was sentenced to 60 days in jail.

Upon release, Kayser dropped right back into a familiar cycle of homelessness, living outdoors, in an RV and with boyfriends over the years.

An escalating crisis

About 20 years ago, Rose helped Kayser move to the Salem area to get away from an abusive relationship. Rose helped her find places to stay with friends, family and at motels, but Kayser burned every bridge she was given by destroying property, berating those trying to help and using drugs.

She ultimately ran out of options and ended up on Salem’s streets, Rose said.

Rose had to stop picking up the phone when Kayser called asking for cigarettes, beer and food. The stress was impacting her own health. She still brought Kayser food when she could.

In the fall of 2020, Kayser was sitting on the sidewalk outside a Nancy Jo’s Burgers and Fries restaurant in Salem. She wore only a blanket.

That’s where Jean Hendron, an independent homeless advocate, saw Kayser for the first time.

“I’m going, ‘Okay. This person’s really stuck.’ And so I stopped, and I recognized right away that Melinda was going to be a little bit difficult to help. She’s pretty ornery when she’s not on her meds,” Hendron said.

Hendron began picking up and replacing Kayser’s dirty diapers and delivering food and clothing, cigarettes and alcohol, believing it best that Kayser not detox from alcoholism on the street.

She soon learned that Kayser had a daughter in town, and reached out. It was November, and it was getting cold. Hendron told Finnegan her mom was in bad shape, staying in West Salem.

When Finnegan picked up the phone to answer Hendron, it ended one of the longest no-contact streaks she’d had with her mother, lasting around two years. She resented the woman who didn’t really raise her, who’d first given her meth when she was a sixth grader, who had accepted help with phone bills and rent but provided nothing in return.

By then, Finnegan was a Realtor, a wife and a mother. She’d been sober nearly a decade. And she didn’t want to see her mom again.

But now that Finnegan knew where her mother was sleeping, she couldn’t stay away. When she found Kayser lying on a sidewalk in West Salem, something in her broke. She couldn’t bear to get out of the car. She called the police to conduct a wellness check.

Finnegan said police soon informed her that Kayser was taken, unconscious, to the hospital. Kayser spent a few days there before being released onto the street again, Finnegan said. From there, Hendron said she moved her into a tent in front of the ARCHES Day Center in downtown.

Hendron called Finnegan again in early 2021. The daughter decided to get out of the car this time to speak to her mom. What she found horrified her.

Kayser had been crawling to a corner of the tent to urinate and defecate, then crawling back to bed. Her feet were gray and gnarled from being constantly soaked.

Her mom also wasn’t yelling at her.

“It’s just insane. It’s one thing when you’re 16 or in your 20s and you see your mom sleeping somewhere but she can still run amok everywhere. Now she can’t – she’s not mobile,” Finnegan said. “She used to be pretty and now looking at her, it’s just really sad to see someone so broken down.”

She began working to help her mother, texting with Hendron to strategize.

Kayser didn’t seem to be aware of her dire condition. Hendron said Kayser didn’t want them to change out the soiled, soaked blankets for new ones.

Video shows Kayser babbling as Finnegan and her daughter, wearing hazmat suits, open the tent and approach her, speaking gently and explaining that they’re going to dress her and get her out of there.

From there, they loaded Kayser into a pickup truck for a trip to a hotel for a bath and fresh clothes. Finnegan didn’t take her home because she didn’t want to scare her younger children.

They then took her to Salem Hospital, where she stayed for several days before being discharged.

After her discharge, Finnegan secured Kayser a spot in a group home. She said the family paid for it at first, then got payment assistance from ARCHES. There Kayser got three meals a day. She received medicine, and was sober from drugs.

Kayser then attended the family’s Thanksgiving dinner for the first time in years. Kayser had always loved her nieces and nephews, Finnegan said, and had been frustrated and confused about being kept from them due to her mental illness.

“She was sitting there just looking miserable because she couldn’t drink, like she was so mad,” Finnegan said. “She didn’t look like she had any energy. But I think that she enjoyed being around everyone. It was the first time she had done it in years and years and years, been able to go and be around people.”

But, the group home didn’t work for long. Kayser began using drugs again, blaming managers and her roomate.

She moved into an apartment on State Street, a building shared with an insurance company.

Finnegan said Kayser couldn’t get herself food and couldn’t pay bills. The insurance workers could hear Kayser screaming from their desks. Finnegan stopped talking to her because Kayser had started using drugs again.

Rose would visit the apartment to clean the place as Kayser’s condition worsened. She picked up soiled diapers and cleaned feces off the floor. She sprayed Raid on the gathering cockroaches. Kayser would yell at her while she worked, saying she already had a professional cleaner doing that same work weekly. She didn’t.

“Melinda, you can’t live like this,” Rose recalled telling her.

The last time Rose saw her sister, she could barely open the apartment door due to accumulated trash. She began cleaning and found a small bag of drugs. When she confronted Kayser about it, her sister attacked her with a crutch while telling her to leave and never come back.

“That was my last straw,” Rose said.

She never visited Kayser again. She thinks about her every day.

Kayser was evicted in May 2024 for not paying $850 in rent, utility and late fees. She had lived there for about a year.

A month later, on June 17, Kayser was arrested for throwing things at passing cars. When officers arrived she was wielding a foot-long metal pipe.

Officer Brian Shaw wrote in his report that many people had been calling police about Kayser, and that officers had brought her clothing several days prior.

“Every time we approached her, she started swinging the pipe around and acting as if she would strike us with the pipe if we approached,” Shaw wrote.

Officers arrested Kayser and took her to jail, according to police records.

“Based on my interaction with Kayser, she is unable to care for herself, and should be in a facility,” Shaw wrote.

That didn’t happen.

On July 25 Marion County’s mobile crisis response team found Kayser under a tree near the intersection of Southeast 21st Street and State Street. She was having “very severe delusions,” according to their report.

She’d apparently torn down a sign warning her that she would soon be banned from the property. She didn’t want to engage with law enforcement, who had requested the crisis response team visit her, and had “no family willing to support her lifestyle,” according to the team’s report obtained by Salem Reporter.

Kayser told the team she’d built the town, and wanted it back the way she’d built it.

The report gave Kayser poor marks on 14 of 15 mental health functions, describing her as unkempt with impaired intellectual functioning and poor judgment.

Kayser declined any help, and was “not able to engage.” The crisis team left her with a business card.

A failed petition

As Kayser’s condition deteriorated, Finnegan hesitated to file a petition to have her mother investigated and hospitalized. Her friends told her it would be a waste of time.

But she believed the only way to save her mother’s life was to have her medicated, sober and stable.

She filed her petition last August. A few days later, Finnegan sat down with Salem Reporter to share her account. Reaching out to every media outlet she could think of was part of this last resort. She felt like no one was listening.

“I’m trying everything that I can. Because I know that after this, nothing will probably happen,” she said, voice wavering as she began to tear up. “I’m going to have to watch her die outside. That’s what’s next.”

Her petition described Kayser’s condition in detail.

“She has been mentally ill seeing things and hearing things for as far back as I can remember as a child and she has been given a chance to care for herself and wasn’t able,” Finnegan wrote. “Now and for about 2 weeks she hasn’t been able to do basic things like walk, change, use the restroom on her own. (She’s) outside naked at times.”

She added that Kayser was bloody from scratching. That she needed a hip replacement. The pins from earlier care didn’t heal properly, she wrote, contributing to Kayser’s immobility along with arthritis.

On the checklist of 14 concerning behaviors, Finnegan checked all but two.

A little over a week later, county investigators said on a form that they’d found probable cause to believe Kayser was “mentally disordered.”

“However, there is not probable cause to believe that the person is dangerous to self or others, or unable to provide for basic personal needs and is not receiving such care as is necessary for their health and safety,” according to a form statement checked by the investigator.

Based on the county submission, a judge dismissed the petition.

Salem Reporter obtained investigatory documents behind that decision. They are typically sealed due to privacy laws, but Marion County Circuit Court Judge Tracy Prall granted the news organization’s petition to open them.

Absent was any documentation of how Kayser established she could care for herself.

Finnegan recalled investigators saying her mom could answer their questions.

Three employees of the county’s behavioral health department, in a joint interview with Salem Reporter, said they work under tight timelines under restrictive yet obscure state rules in deciding whether someone should be committed.

They spoke about their duties in general, and later the county declined to comment on Kayser’s specific case and investigation, citing confidentiality. The investigator who considered Finnegan’s petition was not among those interviewed.

Investigators are trained mental health clinicians tasked with collecting evidence for a commitment, given no more than three days for interviews and observations. They recommend to judges whether there is sufficient evidence to warrant a court proceeding.

They aren’t trained medical professionals, though, which is a challenge when determining whether someone can care for themselves, said Katrina Griffith, deputy director in an email.

“We are not medical professionals to be able to testify that the person’s actions are placing them in danger, and they will expire or experience serious injury due to not being able to care,” she said.

They also serve as the filter for most of the court’s caseload. Last year, of 404 investigations in Marion County, 90% were dismissed before advancing to a court hearing. Of the 40 people who had a hearing before a judge, 26 were committed.

A 2022 study evaluating why civil commitments declined since the process was established by law in 1973 found unclear definitions of civil commitment have been interpreted strictly by the courts. The study said dismissals likely include people who would benefit from commitment.

Ann-Marie Bandfield, project manager of behavioral health crisis services, has worked for the county for over 30 years. She said the civil commitment laws have been on a pendulum swing: it’s either too easy to hospitalize someone or it’s nearly impossible to do so.

Today, she said the system is leaning toward the latter.

“It’s very difficult to prove that someone cannot take care of themselves,” she said.

State training tells investigators that if someone knows they can find discarded food in a dumpster, they’re able to take care of themselves, she said. A spokeswoman for Oregon Health Authority said the agency has not used this as an example since a new unit took over the training in January of 2025.

When Bandfield recalled that guidance, her coworkers scoffed.

“We’re all staring at each other going: ‘Seriously?’ But you have to look at the big picture,” she said. “Do they have medical needs they’re not attending to? Have they been losing weight? Are they covered in feces?”

Marion County Circuit Court Judge Audrey Broyles for years oversaw most of Marion County’s civil commitment cases, and continues to rule on complex cases. She said civil commitments are limited by state law, and the courts’ interpretations of those laws.

“We’ve had years and years and years of deficiencies, and so now we’re in crisis mode, and we’re really not getting the things done that we should have done 20 years ago,” she said. “And now we’re just trying to put a big old Band-Aid on something that is like a gouging wound.”

Broyles read Kayser’s publicly available court files before her interview with Salem Reporter. She shared her personal opinions, not speaking for the Oregon Judicial Department. She said she couldn’t speculate on what may have led to the investigator’s decision.

Still, Broyles found the details Finnegan included in the petition to be “egregious.” She said that the investigator’s opinion that Kayser could care for herself despite having rotting feet and sitting in her own feces was “ludicrous.”

“From what I could read, I don’t know how you wouldn’t find her (unable to care for basic needs) that way. I don’t also know how you wouldn’t try,” Broyles said. “Maybe the judge would say (no), but then let the judge say it. Why wouldn’t you at least try and get her that help?”

“We’re just trying to put a big old Band-Aid on something that is like a gouging wound.”

Marion County Circuit Court Judge Audrey Broyles

For Kayser, the denial was a death warrant.

In November, Finnegan planned to file a second petition, asking investigators to again consider committing her mother.

She wanted to document the exact street name Kayser sat on, so she drove past her on Friday, Nov. 15.

“It didn’t look good. She — there wasn’t any movement. It was weird. Usually you’ll see her talking to herself,” she said.

Finnegan didn’t stop, and feels guilty for that. But some days seeing her mom like that was too much to bear.

“It’s hard for me to see her like that and not be able to help her, take her home,” where, from experience, she couldn’t trust her mom to respect the household rule of drug sobriety. “I try to be nice when I see her, and then I start getting mad like, ‘Mom, why?’”

She instead called the police for a wellness check.

A few days later, an officer knocked on Finnegan’s front door.

Her mother was dead.

In “Sentenced to the Sidewalk” Part 2, posting Tuesday, April 15, learn how the gaps in Oregon’s housing and mental health system play out in Salem Hospital’s psychiatric unit, which has become the only place for many people like Melinda Lou Kayser to receive mental health care. Read Part 2 here.

Contact reporter Abbey McDonald: abbey@salemreporter.com or 503-575-1251.

A MOMENT MORE, PLEASE– If you found this story useful, consider subscribing to Salem Reporter if you don’t already. Work such as this, done by local professionals, depends on community support from subscribers. Please take a moment and sign up now – easy and secure: SUBSCRIBE.

Abbey McDonald joined the Salem Reporter in 2022. She previously worked as the business reporter at The Astorian, where she covered labor issues, health care and social services. A University of Oregon grad, she has also reported for the Malheur Enterprise, The News-Review and Willamette Week.