Editor’s note: This story is a part of a commemorative series marking 30 years since the Oklahoma City bombing, a domestic terrorist attack in which 168 people died. Several stories and multimedia projects commemorating this milestone will be published in the week leading up to April 19, the day the bomb detonated outside the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in 1995.

Correction: This story was updated at 3:14 p.m. on April 14 to correct a reference to Norman High School that was incorrectly attributed as Norman North High School. This story was updated at 9:43 a.m. on April 15 to clarify that Caye Allen has 12 grandchildren and not six and to clarify that Austin Allen did not play basketball for OU.

Families of the seven Norman residents killed in the Oklahoma City bombing reflected on their losses, the community’s response and how they’ve healed 30 years later.

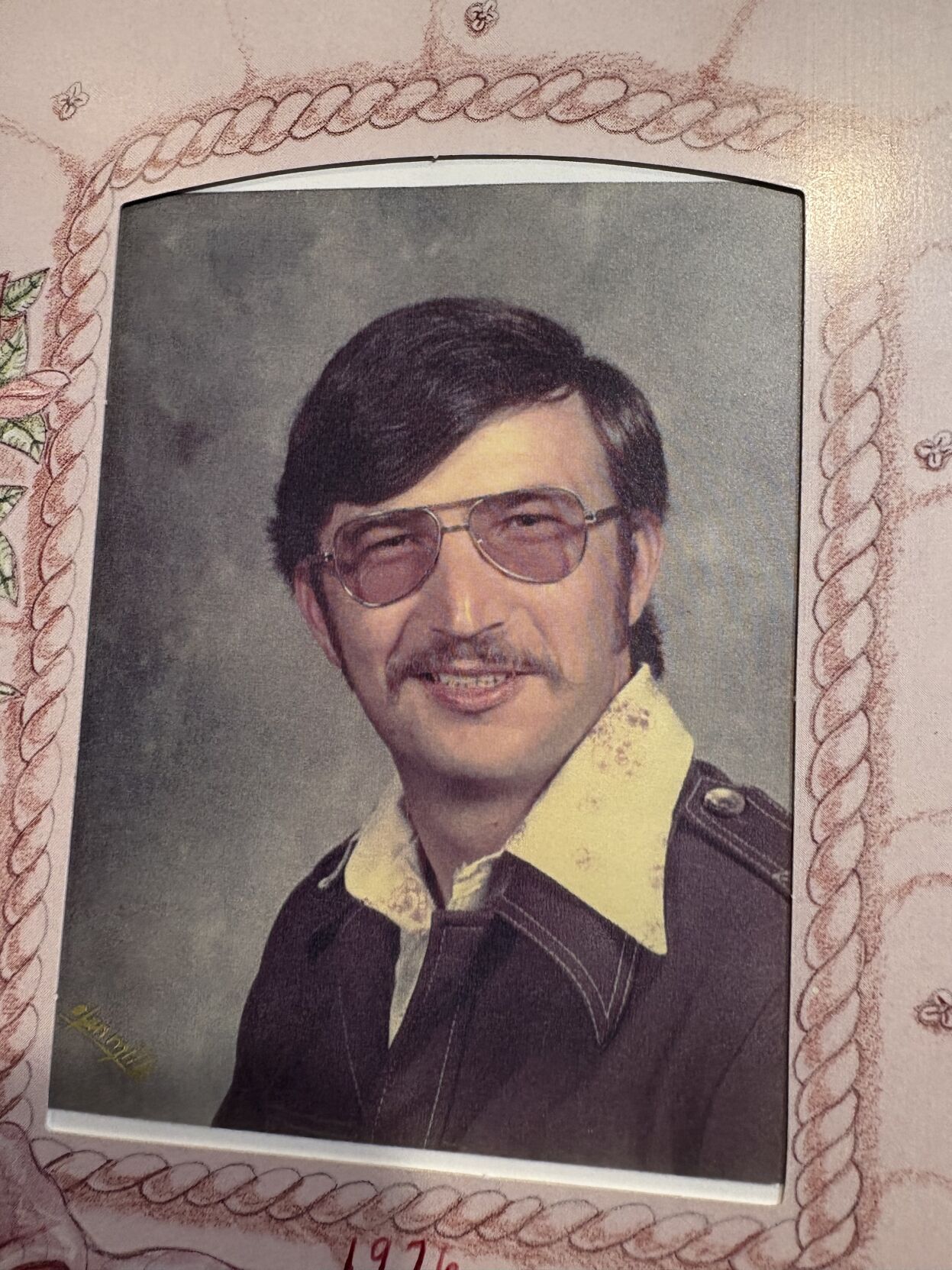

Ted Allen

Oklahoma City National Memorial & Museum chair of Ted Allen on March 30.

Caye Allen put her bagel in the office microwave just after 9 a.m. on April 19, 1995. It had been a hectic morning in the Allens’ house — getting six kids ready for the day was chaos, as it always was.

Caye and her husband, Ted Allen, drove together to work in Oklahoma City, as they often did. She dropped Ted off at the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building, where he worked as an urban planner for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Ted kissed her goodbye and told her he loved her, as he always did.

At the U.S. attorney’s office in the Oklahoma Tower, Caye stood at the microwave as an explosion in the Murrah building, just a few blocks down the street, rocked downtown Oklahoma City.

From the fourth floor, Caye couldn’t tell what happened. Her coworkers thought the blast might have come from the nearby courthouse. She remembered thinking, “Man, do I have a story to tell when I get home.”

Caye and a friend walked down Harvey Avenue to the site of the blast. The ground was covered in glass, debris, paper — and the bagel Caye quickly cast aside.

It was eerily silent, she said, until alarms began to sound. They echoed off the high-rise downtown buildings, reverberating in her head. Police wouldn’t let onlookers see the back of the building, where the bomb had detonated, because it was too hot. Nearby cars were ablaze.

Around them, people sprang into action, helping the wounded away from the blast site.

“I thought, ‘OK, that would be (Ted’s) instinct.’ I knew in a heartbeat that's what he'd be doing,” Caye said. “‘Or maybe he's trapped in a stairway because he was on the eighth floor,’ and so I thought maybe he's trapped in a stairway.

“I had hope.”

Caye spent the rest of the day in a holding area in the basement of a hospital and then in a church, waiting for news of Ted.

No news came.

“I thought, ‘OK, he's hurt, but they'll get to him,’” Caye said. “I told myself to stay sane, that everything was going to be OK.”

When she arrived home around 10:30 p.m., Caye finally saw the damage to the back of the Murrah building on the evening news.

“Once I saw that, I knew,” Caye said.

Ted’s office was in the rubble.

“I never said a word to the kids and never said a word to anybody because I wanted everybody to keep hope,” Caye said, her voice breaking. “You just never know. I wanted everybody to keep hope.”

Caye, however, had lost all hope. After a week, the Allen family was notified that Ted had died in the blast.

Caye knew 45 people who died that day.

‘He loved seeing them happy’

Caye and Ted met on their first day working for the Department of Housing and Urban Development a decade before the bombing when they were both married to other people. Every day, the two carpooled with three others from Norman to work in Oklahoma City. They both eventually left HUD and didn’t see each other for over five years.

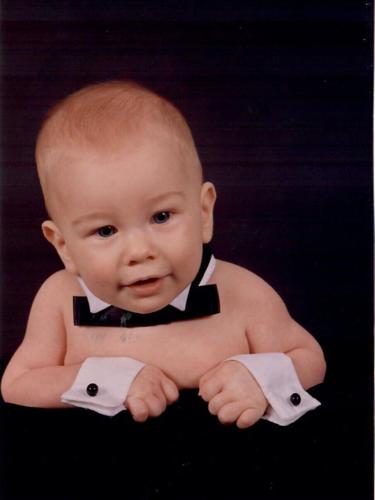

Then Caye and Ted, both divorced, reconnected at a New Year’s Eve party and began dating soon after. The couple married in 1989 and joined their five children — Spencer, Jill, Gretchen, Meghan and Rachel — into one family. They had a son, Austin Allen, together in 1990.

Ted Allen, center, surrounded by his children. This is the last family photo of the Allens, taken in Dec. 1994.

Ted was the “ultimate dad,” Caye said, who coached kids’ sports and was a remarkably caring man. He loved to laugh at himself and had no ego, she said.

Ted worked as a city planner in Moore before returning to HUD. He was passionate about affordable housing and helping people who experience homelessness, Caye said. The couple worked together to find places for people to stay when the weather was bad and shelters were full, with Ted calling around on one phone and Caye on another.

“He helped people, and he enjoyed the result,” Caye said. “He loved seeing them happy.”

Their youngest child, Austin, was 4 when Ted died. Caye told him what happened to his dad a few days after the bombing, but it was hard for him to understand.

The day of the funeral, when they were supposed to be leaving for the church, Caye couldn’t find Austin. She walked into his room and found him lying on his bed in his formal black suit.

“I said, ‘What are you doing? Let's go,’” Caye said. “And he said, ‘I'm showing dad my suit, and I have to lay down or he can't see how good it looks.’

“30 years later, I can't even talk about it,” she said through tears. “It was huge. He was 4, he really didn't even understand death.”

While his memories are few, Austin remembers the house was full of people in the weeks following the bombing, which made him feel loved. Over 1,000 people attended Ted’s funeral. Austin said the community support continued as he grew up, and teachers treated him with extra care and tenderness.

“It’s in the midst of tragedy, but we've had a lot of good people around us,” Austin said.

Caye Allen, wife of Ted Allen, holds their son Austin Allen at Ted Allen's funeral.

Caye said friends and neighbors delivered lots of food, mowed their yard and decorated their mailbox with yellow ribbon, which became a symbol for remembering victims of the bombing. The family received letters from around the world and cards from elementary schools, and the kids’ friends would sleep over every night so they wouldn’t be alone.

“It restored my faith in humanity,” Caye said.

Losing Ted made Caye a more forgiving parent, she said, because she learned the arguments and rules she used to be strict about wouldn’t matter the next day.

“I used to tell them, ‘Don't get mad about it now,’” Caye said. “‘You can wake up tomorrow and your life has changed forever. Don't let little things like this get in your way of happiness.’”

Caye said her family decided they weren’t going to live as bombing victims or let the actions of Timothy McVeigh, the man convicted and executed for orchestrating the bombing, destroy them.

After the bombing, Caye continued to work in the civil division of the U.S. attorney’s office while the criminal division prosecuted McVeigh. The prosecution was dedicated to carrying out justice and did incredible work, Caye said.

Later, Caye met Oklahoma State Trooper Charlie Hanger, who had pulled McVeigh over on Interstate 35 in Noble County for not having a license plate. Hanger discovered McVeigh had an unregistered gun hidden under his jacket and arrested him, which led to the FBI identifying him as a suspect a few days later. Caye said she sees Hanger as a hero.

“We weren't going to let Tim McVeigh ruin our life,” Caye said. “He ruined 168 — I'm just not letting him ruin mine, too. That's what he wanted, he doesn't deserve that. He's not worth my time.”

Losing his dad taught Austin that life is short and can end at any moment. He said experiencing that tragedy made him stronger.

With financial aid from the Oklahoma City Community Foundation, all six of the Allen kids graduated college. Caye said their college admissions would have been a big deal to Ted because he was the first person in his family to graduate college.

Austin graduated from Norman High School and went to OU.

Thirty years after the bombing, Austin is 34 and a realtor. He and his wife, Marissa, live in Norman and have a son, Avery, and daughter, Sadie. Avery turned 4 in September.

This anniversary is especially emotional for Austin. He said he has been anticipating for years how hard it would be to see his own son at 4 years old — the same age he was when his dad died.

As Austin thinks about his son, he sees his dad’s death from another perspective.

“What if I just didn't show up?” Austin said. “What if I was gone tomorrow? How would that impact Avery?”

Austin said his bond with Avery is similar to how his relationship with his dad was, and he sees his 4-year-old self in Avery. Austin said he’s excited to watch Avery grow up and spend those years with him as a dad — years he didn’t get to spend with his own father.

Austin Allen and his wife Marissa hold their son Avery at the Oklahoma City National Memorial and Museum after the 2023 memorial marathon.

Austin said he and his wife wrestle with how to tell Avery what happened to his grandfather. He wants to preserve his son’s innocence because he remembers how he lost his.

“He was 4 years old, and here he is, a grown man with a 4-year-old of his own,” Caye said. “You really realize how much time has passed and how much has happened.”

Caye now has 12 grandchildren, which she said Ted would have loved to know. She said she hates he wasn’t there to walk any of his kids or grandkids down the aisle at their weddings.

“I’ve had a wonderful life. I wish it hadn't come out this way, the way it happened and everything,” Caye said. “But I've had a really good life.”

Austin said he knows his dad would be proud of him.

“I would love to have my dad here, but at the same time, I wouldn't change anything,” Austin said. “(I’m) super happy with my family, super happy with everything that I've accomplished.”

Ted loved his country, Caye said, and ultimately died for it.

“I want people to know my husband,” Caye said, “I want them to know Ted Allen, I don't want them to know the 77th body they found that happened to be in the building that day.

“I want them to know his life.”

Ted’s chair in the memorial is the first chair in the eighth row from the Reflecting Pool.

Kevin Lee Gottshall II

Oklahoma City National Memorial & Museum chair of Kevin "Lee" Gottshall II on March 30.

Kevin Lee Gottshall II, who was called Lee, loved Mickey Mouse, dancing with his mother and “Old Time Rock and Roll” by Bob Seger. The only thing he truly hated was green beans.

His parents, Kevin and Sheryl Gottshall, first met in the Kerr-McGee building, now called Strata Tower, when they ran into each other in Kevin’s office. Sheryl was on an errand to deliver a file to Kevin’s desk and slammed into him as she turned around. They married two and a half years later.

The couple meticulously planned to have their first child and built a home in Norman with a nursery and room for him to play. Kevin and Sheryl chose the most secure daycare they could find — the America's Kids Child Development Center in the Murrah building.

Six-month-old Lee could roll over, was fascinated by pinwheels and never fussed, Sheryl said. Lee was named after Kevin’s grandfather Lee D. Long, a calm man who taught Kevin how to fish and many other life lessons, he said. Lee was Grandpa Lee’s first great-grandchild.

“We would just be looking at (Lee) and can tell he was really thinking something,” Sheryl said. “So we call him the ‘deep thinker.’ It was like he had an old soul. … It was a blast having him.”

Kevin Lee Gottshall II was six-months-old when he died in the Oklahoma City bombing on April 19, 1995.

Lee had blond hair, six teeth and looked most like his father, Sheryl said.

The morning of April 19, 1995, the couple dropped Lee off at daycare and arrived at the Kerr-McGee building for work, just a block and a half away from the Murrah building. It was just past 9 a.m. on a warm, sunny morning.

Suddenly, all the first-floor windows shattered around Sheryl. While her coworkers ducked under tables, Sheryl jumped through a broken window and ran for the Murrah building.

The south side looked normal, Sheryl said, except for concrete flowing out of the doors. A police officer kept her from entering despite protests that her son was inside.

Kevin soon joined her, and when they walked around to the north side of the building where the bomb had detonated, they knew what had happened to Lee.

“Whenever you find out that your infant son, your firstborn, is most likely dead, what would you expect would go through your mind?” Kevin said. “How does it change your life, that you have a child and then you don't have a child?

“It's devastating, and it will change your life forever.”

The couple waited in a Red Cross holding area for news of Lee. None came, so they went home. Two and a half weeks later, Lee’s body was identified.

Kevin and Sheryl had been looking forward to celebrating Lee’s first birthday. Instead, they took down his nursery and planned his funeral.

Kevin Lee Gottshall II Memorial Park on April 8.

The headstone at Lee’s grave has a picture of Mickey Mouse, and the inscription reads that he filled his parents’ lives with joy.

“Your smile, laughter, and wonderful hugs will always be a part of our hearts,” the headstone reads. “We miss you sweet pea. Love, Mom and Dad.”

‘We weren’t going to give up’

The Gottshalls grieved privately, which they said helped them avoid some of the attention surrounding the bombing. Kevin said they realized their only option was to move forward, and soon after the bombing the couple moved to Houston.

“We knew we couldn't do anything better than him, and we hoped to try to go on with our lives and honor him that way,” Kevin said.

Sheryl said after the bombing, some couples who lost a child didn’t stay together or have any other kids, but the Gottshalls didn’t give up. Their resilience honors Lee’s memory.

“With him, we’d say, ‘For your first birthday, we’ll get a brother or sister,’” Sheryl said. “(Even) then, we were planning for more kids, and we weren't going to give up and let that evil win.”

In February 1996, Kevin and Sheryl had their daughter, Elizabeth Lee. In October 1997, their son Kevin Lee Gottshall III was born.

As Elizabeth and “Little” Kevin grew up, their parents told them about Lee, often showing them photos and answering their questions. The family visited his gravesite and the Murrah building.

“What would our lives have been like? How does it change your life?” Kevin said. “Well, if our current children had had an older brother, what would he be doing? How could he have helped or influenced their lives? And they had him — he was just taken away.”

A development company called Westpoint Homes named a lake in Norman after Lee and installed a plaque made out of granite from the Murrah building in the summer of 1995. Soon after, the city-owned park across the street was named the Kevin Gottshall II Memorial Park.

Kevin Lee Gottshall II Memorial Park on April 8.

The Norman community loves the park, Sheryl said, and it’s calming for her to visit. Kevin said it’s a place where families can see happiness, which encourages him to remember good people exist.

Both of their children attended OU, and the park became a part of their lives, Sheryl said. Members of Elizabeth’s Alpha Phi sorority and “Little” Kevin’s Phi Delta Theta fraternity would go with them to the park to pull weeds, water the flowers and decorate for Lee’s birthday.

“It's a really wonderful reminder of how good people are because your mind goes immediately to the tragic event and how evil these people can be and are,” Kevin said. “And on the other side of that, of how many people in Norman and from around the state and the country stepped up to reach out to us.”

The Gottshalls received letters and mementos from across the country and said they felt supported by their community. Even 30 years later, Betty Lou’s Flowers & Gifts continues to deliver flowers to Lee’s gravesite for every holiday, which is a relief and comfort, Kevin said.

When Elizabeth got married and had a child, she and her husband named him Bennett Lee Reina. Bennett is now 2 years old.

Kevin and Sheryl miss Lee every day and said they try to live in a way that respects him.

“It's not like you have to make a point to remember him,” Kevin said. “You remember him all the time.”

Lee’s chair in the memorial is the 13th chair in the second row from the Reflecting Pool.

Steve Curry

Oklahoma City National Memorial & Museum chair of Steven Douglas Curry on March 30.

During passing period at Central Mid-High in Norman, Jay Curry walked through Boyd Hall to make it to his second period English class on time.

Jay was 14 and a freshman in high school with excellent grades. He loved sports and was a standout on the school basketball team.

“Did you hear some terrorists blew up a building in downtown Oklahoma City?” Jay overheard someone ask as he passed through the double doors.

Jay knew his dad, Steve Curry, worked in that area but didn’t think anything of it.

After the bell rang, Jay’s English teacher, Ms. Savage, read a statement from the school: There was an explosion at the Murrah building. Next to him, a girl in his class said her dad, who had gotten Jay’s dad his job, worked in that building.

Then, he realized — his dad must be in that building.

“My heart dropped,” Jay said.

Jay’s older sister, Jennifer, was a senior at Norman High School and picked him up from school early, though she could hardly drive through her tears. When they arrived home, they found their driveway and front lawn packed with cars.

Family, friends and church members clustered around TVs turned to different news stations, hoping to catch a glimpse of Steve’s gray pants and black shirt. They didn’t see him, and Jay said his mom was distraught.

Later that day, Jay’s mom and a few other family members went to St. Anthony Hospital, frantically searching for Steve, but they couldn’t find him.

Meanwhile, Jay continued to watch the news, hoping more survivors would be discovered. He couldn’t sleep that night.

Around 3 a.m., the dentist called to ask if he could release Steve’s dental records, which the family realized was not a good sign.

Two days later, the Currys were notified that Steve had died.

‘That’s the kind of person my dad was’

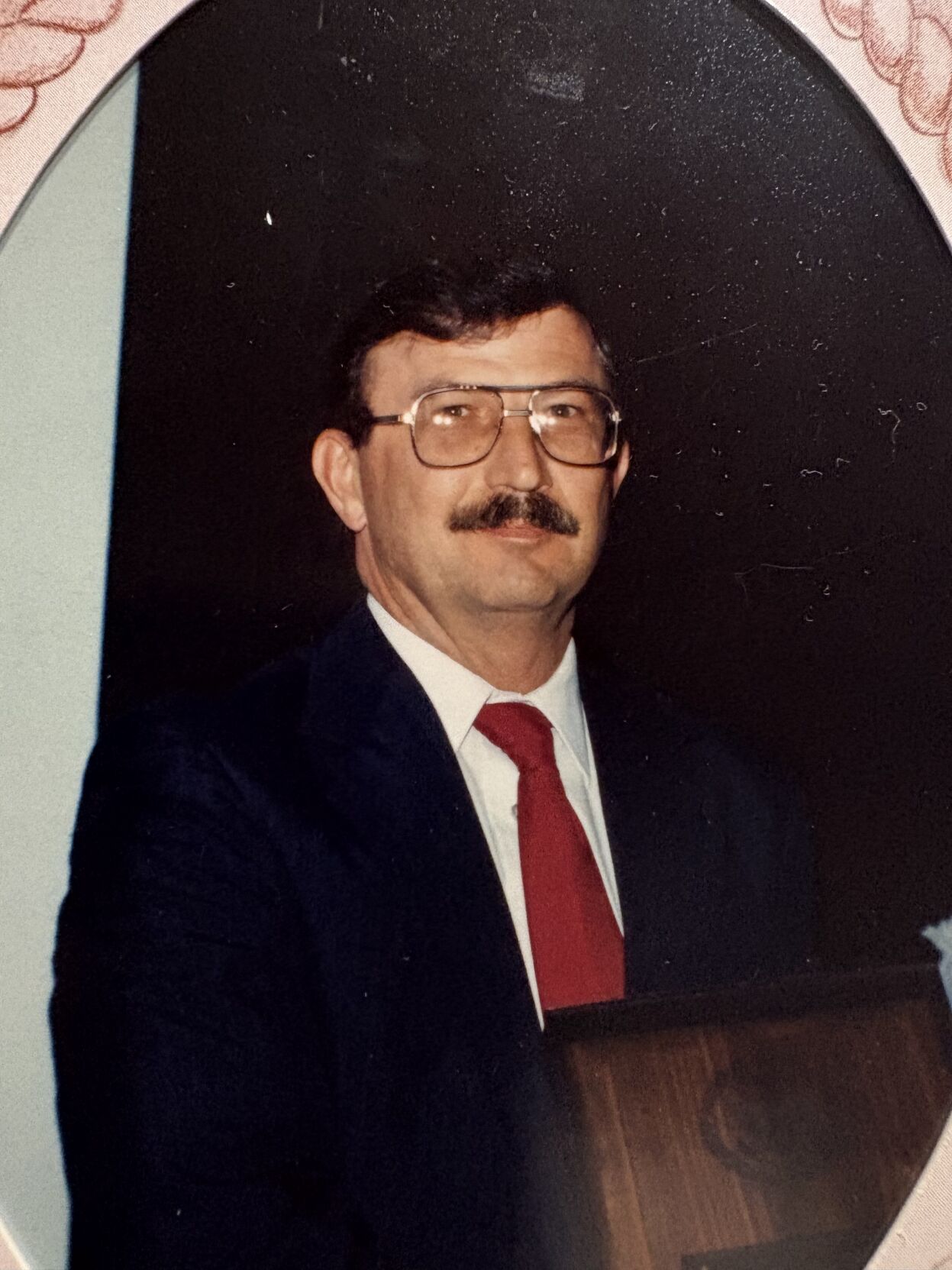

Steve grew up in Choctaw, and after graduating high school, he served in the U.S. Navy from 1969-74. He met his wife, Kathy, on a blind date in 1973, and the two got engaged six weeks later. Steve and Kathy married and settled in Norman in 1974 and had two kids, Jennifer and Jay.

Steve worked as an electrician and federal building inspector for the General Services Administration. He served as a deacon at Calvary Free Will Baptist Church and coached the church basketball team, passing on his love of basketball to Jay.

Jay said family was incredibly important to his dad. The Currys lived on a 25-acre plot surrounded by Jay’s grandparents, uncle, aunt and cousins.

Jay said Steve loved to help others, whether that meant installing a friend’s ceiling fan or rewiring their house. He loved to talk to people and was a great listener, which made for some long afternoons after church waiting for Steve to be done catching up with friends, Jay said.

“He had a big heart and didn't make a lot of money, but he made a huge impact on people and, in my eyes, was just a superhero,” Jay said.

Community members brought the Currys food every day for months and took care of all the funeral proceedings. People from across the country would send cards and gifts, and the response was so positive that it was overwhelming, Jay said.

Steven Douglas Curry, right, and his wife Kathy Curry in 1974.

Jay said nearly 3,000 people attended Steve’s funeral.

“If it wasn't for our church family and friends and direct family, I don't know how you would make it (and) not come out bitter after what happened,” Jay said.

After the bombing, Jay’s grades slipped and he quit basketball. He said he didn’t know how to process his dad’s death and didn’t want to be known as “the kid whose dad was killed,” so he pushed down the memories.

“I didn't know why all this was happening. I just didn't process everything,” Jay said. “Looking back, it's like the most important person in your world was taken from you, and that's why all of that happened.”

Jay said he lost his direction in life. He graduated high school and went to college at OU but found himself floundering. His friends were graduating and moving on, but he was stuck. Jay used to dream of leaving Norman, but following his dad’s death, he couldn’t leave his family — specifically his mom, Kathy.

In the middle of Jay’s spiral, Kathy found Steve’s old diary and read an entry from 1994: Steve had planned to go back to school and get a teaching certificate. He was amazing with high school kids and wanted to teach electrical work.

“Why don't you fulfill what your dad wanted to do and you become a teacher?” Jay remembered his mom asking.

Jay got his teaching certificate and said he found new purpose and joy in teaching.

Soon after, Jay met Megan, who had lost her dad when she was a senior in high school. They bonded over their struggles and helped each other heal — they’re now married with two kids.

Jay and Megan’s daughter is named Lillie and their son is named Steve Lawrence after both of their late fathers.

“I tell my kids, you're gonna go through struggles,” Jay said. “What's important is to surround yourself with people who love you and will take care of you. That's the kind of person my dad was.”

The Currys live on the same 25-acre plot that Jay grew up on, still surrounded by family.

Jay has been teaching video production and helping run student council at Norman North High School for 25 years. Megan also works for Norman Public Schools as the district transition specialist, where she helps students with disabilities increase their job skills and opportunities.

Each year on the first day of school, Jay tells the new students in his video production class his and his dad’s story.

“I've fully embraced what happened, and I want to tell the world about it,” Jay said. “I enjoy telling people about what happened, just so it's an event that doesn't disappear.”

Jay said teaching feels like hanging out with his best friends because he loves his students so much. He works to make a difference in their lives by being a person to confide in, the way his dad was for him. Each day, students come to Jay’s classroom during their free time or lunch periods.

Steve’s dad wasn’t loving, Jay said, leading Steve to make sure his kids knew he always loved them — and they did.

Jay always tells his children he loves them, too, because he has seen how quickly life can end. Jay is now 44, the same age his dad was when he died.

“My parenting philosophy is just fill a house full of love because you don't know when you're gonna not be there,” Jay said.

Jay and Megan teach their kids to treat others “like Grandpa Steve did” and continue his legacy by telling others about him. Steve wasn’t rich, but he loved people well, Jay said.

“I've fashioned my life after my dad,” Jay said. “His family was incredibly important to him. He was a guy who couldn't say no to anything.

“He had a huge heart.”

Steve’s chair in the memorial is the 41st chair in the first row from the Reflecting Pool.

Four other people from Norman died in the Oklahoma City bombing. OU Daily was unable to get in contact with family members of these victims. The following stories are pieced together from existing obituaries and exhibits in the Oklahoma City National Memorial and Museum.

Betsy J. (Beebe) McGonnell

Oklahoma City National Memorial & Museum chair of Besty J. "Bebee" McGonnell on March 30.

Betsy J. (Beebe) McGonnell attended OU to study history and English, which is where she met her husband, Owen. The couple had two children, William and Jamie Cathleen, who Betsy stayed home to raise.

When her children got older, Betsy began working at the Department of Housing and Urban Development in the Murrah building as an assistant loan manager.

Betsy loved music and was a talented alto singer, the memorial reads. She was an active member of St. Michael’s Episcopal Church and sang in the choir.

Betsy’s chair in the memorial is the 14th chair in the seventh row from the Reflecting Pool.

Gene Hodges

Oklahoma City National Memorial & Museum chair of Thompson Eugene "Gene" Hodges Jr. on March 30.

Thompson Eugene Hodges Jr., who went by Gene, and his wife Deb had four children. Gene was significantly involved with his kids’ Little League Baseball, judo and scouts and coached his 5-year-old son’s soccer team.

As a coach, when kids made mistakes, Gene would use it as a teaching opportunity instead of pulling them out of the game. Gene understood that everyone made mistakes, Deb said according to the memorial.

Gene was a supervisor for the Department of Housing and Urban Development in the Murrah building.

Gene’s chair in the memorial is the ninth chair in the seventh row from the Reflecting Pool.

Jerry Lee Parker

Oklahoma City National Memorial & Museum chair of Jerry Lee Parker on March 30.

Jerry Lee Parker grew up in Oklahoma City and studied civil engineering at OU.

After Jerry married his wife, Sharon, in 1968, the couple lived in Enid and Topeka, Kansas, before settling in Norman in 1985. They had three children: Sharissa, Michael and Michelle.

Jerry was a member of Pleasant Hill Free Will Baptist Church, where he served on the board and taught Sunday school.

“God and family were the two most important things in his life,” his biography at the memorial reads.

Jerry was a civil engineer for the Federal Highway Administration in the Murrah building. He was proud to be a federal employee, according to the memorial.

Jerry’s chair in the memorial is the seventh chair in the fourth row from the Reflecting Pool.

Oklahoma City National Memorial & Museum chair of Claude Arthur Medearis on March 30.

Claude Medearis

Claude Medearis was a senior special agent with the U.S. Customs and Border Protection Agency office in the Murrah building.

Claude’s chair in the memorial is the 10th chair in the fifth row from the Reflecting Pool.

This story was edited by Peggy Dodd, Anusha Fathepure, Ana Barboza and Ismael Lele. Andrew Paredes, Avery Avery, Gretchen Schultz, Sophie Hemker, Grace Rhodes and Mary Ann Livingood copy edited this story

30 years later: OU, Norman communities reflect on Oklahoma City bombing

Comprehensive coverage on the legacy of the Oklahoma City bombing 30 years ago.