Carlos Batista has worked at Orlando international airport for 12 years as a wheelchair attendant, a job where he often doesn’t make the federally required minimum hourly wage because he is classified as a tipped worker. Instead, the independent contractor he works for pays him $5.23 an hour, and attendants are not allowed to solicit passengers for tips.

“A lot of people don’t know we live off tips, so we get thank yous, and the average wheelchair assist from counter to gate takes 45 minutes to an hour,” Batista said. “We’re the face of the airport. We take care of mothers and family members who need assistance with wheelchairs and bags.”

Due to his low wages, Batista can only afford to rent a room from his uncle. He said high baggage fees now meant air travelers carry less luggage, resulting in fewer tips while his wages have remained stagnant.

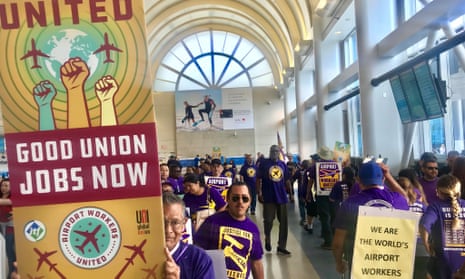

Batista’s problems – and those of thousands of workers like him – are symptomatic of the air travel industry. As the airlines and airport companies seek to boost profits, they have increasingly relied on low-cost air carriers and contractors that drive down wages, eliminate benefits and infringe workers’ rights, according to a recent report by Airport Workers United.

The report noted airlines made $38bn in profits during 2017, a fourfold increase since 2013. Nearly half those profits are made by US-based airlines. The International Air Transport Association predicted in 2018 expenditures on air travel would grow by more than $70bn.

The airport industry is also booming from an increase in airline passengers. In 2016, global airport revenues were over $160bn, with 39.4% generated from sources such as retail concessions and parking. In 2018, US airports experienced a record number of air travelers for the summer and Thanksgiving holiday.

But those profits do not trickle down to the workers that generate them. In the United States, airports have cuts jobs and outsourced them to contractors despite increases in the number of travelers. An October 2013 study conducted by the Labor Center at the University of California, Berkeley found that between 2002 to 2012, outsourced baggage handler jobs increased from 25% to 84%, while wages during that period for baggage handlers dropped by more than 45%.

Another example is 67-year-old Aleida Diaz. She started working at Orlando international airport this summer as a wheelchair attendant when she decided to stay in Florida after Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico, where she worked as an English teacher.

“Sometimes you don’t even make the minimum wage with the tips,” Diaz said. She too makes $5.23 an hour plus tips. “It’s very hard because I have to eat, pay my rent, my electric bills, and I’m barely making ends meet.” Her son is going to be deployed to Afghanistan on 2 January, but the independent contractor who she works for did not allow her to take time off to spend with him due to the busy holiday season.

In 2003, customer service agent Janice Woods’s employer at Miami international airport switched to an independent contractor. She makes around $15 an hour, but her hours and benefits were drastically cut. “They cut hours to make us part-time,” Woods said. She has worked at the airport for 19 years. “They used to offer vacation, sick days, health, dental, vision and flight benefits.”

The contractor eliminated benefits, and her healthcare plan now has a hefty deductible. Woods added, “I was sick last year and the beginning of this year. If it wasn’t for my family to come up and pay my bills … I wouldn’t have been able to make ends meet.”

Klassie Shepard, an airplane cabin cleaner working for an independent contractor at San Francisco international airport, has also struggled even though San Francisco raised its minimum wage to $15 an hour.

“In 2017, working full-time at SFO, I was homeless. I would sleep at the airport on the blue chairs in the terminals with a blanket over me,” Shepard said. “I wasn’t making enough to be able to afford rent by myself.”

In November 2018, Shepard was fired. Her employer said she walked off the job but Shepard explained she felt dizzy, tried to call a supervisor who didn’t answer and then flagged down a police officer who called an ambulance and took her to hospital. Shepherd, with help from the Service Employees International Union, is working to get her job back.

A spokesperson for San Francisco airport said: “Our records show medical personnel being dispatched to an airport service company break room around that date and time, but we do not have any additional detail on the circumstances.”

Low wages and poor benefits in the airport industry have contributed to thousands of airport workers relying on government assistance. A June 2017 report published by the Economic Roundtable found that more than 116,000 US airport workers receive food stamps, more than 23,000 received cash welfare benefits, and over 194,000 out of roughly 664,000 airport workers in the United States rely on Medicaid.

Mark Souder, who has worked maintenance at Baltimore-Washington airport for eight years, used government assistance to help pay for his prescription drug medicine when a new independent contractor, Menzies Aviation, took over and changed his health insurance plan. Under the new plan, specialty medication was not covered, leaving Souder, who is HIV positive, to figure out how to pay for his pills.

“It was covered for seven years, then Menzies took over,” Souder said. The Maryland Aids Drug Assistance Program eventually agreed to cover his medication costs for a year, but Souder is unsure what is going to happen when that ends on 31 December. He could face crippling costs or a lack of vital medicines.

Orlando international airport did not respond to requests for comment. Miami international airport and Menzies Aviation also did not respond to a request for comment.